by Douglas Kolacki

Josiah Williamson crouched at the bulwark, peering through a brass telescope at the merpeople. They darted in and out of the rolling Atlantic with such grace that they barely made splashes. Their skin, oyster-white, reminded him of sperm whales—did layers of blubber warm them as well?—and hair black as the depths, streaming over their shoulders or down their backs.

Serrated fins, not unlike sailfish’s, grew from each forearm (he had read about those), and unlike in the fairy stories, the sea people had no fishtails but legs, with feet—there!—only slightly webbed. The mermaids, noticeably smaller, lacked the forearm-fins and displayed small, nippled breasts. Mammals, then—warm-blooded, young-nursing . . . air-breathing. Young ones like baby porpoises had been sighted from time to time, but Josiah saw none here.

He lowered the spyglass. The Copernicus heaved, rising and falling beneath his boots. Cupping a hand to his mouth, he shouted: “Hey there, gente del mar!”

Christopher Columbus had called them that—”sea people”—when he sighted them in 1496 some forty leagues off Gilbraltar. Williamson replaced the cap on the telescope.

“If Columbus had seen all females he might have called them sirena, and we’d all be thinking now that they sang out to the Virginia’s crew and lured them to their doom.”

Damn it all to hell. If they wanted an iron ship, why not the Federal one? The one John Ericsson built for them—Williamson now knew they’d named it the Monitor—had been in the area. Why ours, when we’re at such a disadvantage already? Why do it at all?

For the third time since hauling bottles and books and violin onto his two masted-schooner and setting out, he took a deep breath and reminded himself: this is an opportunity. A golden opportunity for the South, for the abolition-obsessed North, for the house divided that our country has finally become.

The merpeople could now be tracked.

###

Williamson went below.

He had crammed everything from his Wilmington, North Carolina study into the great cabin aft: bookshelves with crumbled tomes such as Aula lucis or The House Of Light, The Six Keys of Eudoxus, John French’s The Art Of Distillation, Pontanus’ Epistle On The Mineral Fire; glass beakers sloshing with amber or clear liquids on a potbelly stove, and tubes snaking up from two of these through the overhead. Wooden racks held bottles of whiskey, brandy and bourbon, as well as thin glass tubes containing various measured amounts of powdered blood. Exactly where the blood came from, he never said.

His desk was the size of a door and littered with sheet music. Some of the papers would slide off and flutter to the deck when the ship rolled, and Williamson, muttering, would gather them back up.

Against the far bulkhead was a high-backed chair, and in it sat a weathered old Negro, lanky as Lincoln, snowy hair crowned with a top hat. He did not move when Williamson entered.

Williamson picked up his violin and bow. “Damned if they weren’t abaft the port beam, Daniel, just like you said.”

The Negro did not stir. Williamson, plucking and tuning the strings, looked out the window at the heaving waves and thought: Daniel sees none of this. Not the sun, the spray . . . instead, he sees where our eyes can’t go.

But can he sight the wreck?

###

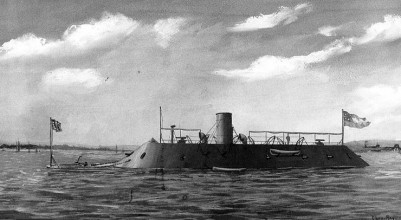

The CSS Virginia: once the fifty-eight-gun frigate Merrimack, burned and scuttled in a panic by the Federals at Norfolk Navy Yard when Virginia seceded.

America had been considering ironclads since the War of 1812. Now, for the Confederacy and the charred Merrimack, the time had come. She had burned only to the waterline; her machinery remained intact. The Navy raised her, restored her, built a casemate angled at forty-five degrees to deflect enemy fire. They re-armed her with ten guns, a seven-inch pivot-mounted rifle at each end, a battery of two six-inch rifles and six nine-inch smoothbores, and an iron ram fixed to her bow.

And on March 8, 1862—ten days ago—the Virginia, along with the gunboats Beaufort and Raleigh, set out from Gosport Navy yard up the Elizabeth River. Ready to avenge herself! Smash the wooden blockade!

But something had happened. Water boiled all around the ironclad, as if suddenly heated, and creatures like albino swimmers swarmed up over the casemate. Both gunboats saw a puff of smoke, followed by the boom of one of Virginia’s cannons. This happened a second and third time. By now the white swarm covered her completely, and she accelerated to a speed faster than her normal six or seven knots, churning up a fearful wake as she sped away, past the Sewell’s Point battery and out to sea.

The entire South buzzed with the speculation: have they sided with the Federals?

###

Williamson measured an amount of whiskey into one of the beakers. To this he added another few shreds from a wool undershirt worn by (so his widow had said) Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan, the Virginia’s commander. Then he opened the stove door and blew on the coals. The liquid bubbled, boiled, vaporized into fumes that drifted in the cabin, sharp with alcohol and certain additional elements. Still no movement from Daniel, but Williamson knew he was breathing it in. Williamson selected a Bach concerto from the sheet music littering his desk, played, and waited.

After a while, Daniel spoke. “I see it, Mr. Josiah.”

The violin notes stopped. “Where?”

Daniel, as he nearly always did, paused before answering, as if to let the question sink into his mind where the answer would formulate itself and rise to his consciousness.

“No. Sorry. Might have for a minute, but it slipped away from me.”

The Captain frowned. It might have made a difference if he had left Wilmington sooner.

More whiskey in the beaker; thicker fumes. Williamson almost, not quite, coughed. His eyes stung, watered, but he couldn’t do much about that. He sat down on his desk, balancing against the heaving of the ship, and resumed his concerto.

Another half hour would pass before Daniel spoke again. “It’s on the bottom, sure as anything. I saw it some minutes ago, but I wanted to be sure before I told you. It’s just sitting, don’t look like they plan on taking it anywhere.”

“What about our friends?” Williamson played on.

“Well, Mr. Josiah, that’s the funny part. There’s mer-folk all around it, maybe hundreds of’em . . . never seen that many before in one place . . . but it’s all bright, like the ship’s on fire.” The slave hesitated, his brow ever so slightly creasing. “No. It’s. . . .”

The Captain stopped playing. “The merpeople who are on fire?”

“Yes. Or some of them.”

Williamson had read of these also, a species like electric eels or undersea suns, appearing always to burn. Possibly absorbing the ocean phosphorus.

Daniel gave the Captain a rough heading—southeast, more or less. “Think maybe you can raise it up, Mr. Josiah?”

The Captain, violin in his lap, was calculating how long the journey would take if he manipulated the western Atlantic winds to gust full force into his sails, how much liquor he would have to boil and pipe up topside in order to do this, and if what remained Buchanan’s undershirt would suffice to lead him to the wreck’s exact location. Williamson had wanted two pieces of clothing, but the widow wouldn’t cooperate, foolish woman. Raise it up?

“That’s not so much my plan.”

That, he’d kept to himself.

###

Since Columbus’ time, merpeople had been sighted off Bermuda, the Azores, and at various points in the deep Atlantic. Whalers from New Bedford and Nantucket had tried to capture them, but they were not so huge or ignorant as those great beasts; they darted away, nimble as dolphins, before anyone could even lower a boat.

But Daniel saw things. With the right chemistry, he could search out the hidden and lay it bare. And when Williamson got close enough to bring his own talents to bear . . .

Perhaps, at the cost of its ironclad, the South could transform like the Merrimack itself.

Could this be America’s salvation? For centuries men believed Africans were the beasts of burden, but now nature showed them their error. They had looked to the wrong place. The true slaves were not creatures of land, the land shared by all men, but beings strong enough to withstand even the crushing ocean depths. Capturing them, bringing them home for all to see, could make the difference. Compared to them, the Africans and all men stood revealed in their true human light. Everything could change!

So Williamson wondered: how strong are the merpeople, to haul off a 3200-ton warship? How hardy? Would they prove more difficult to shackle than Africans? Would they shrivel up if kept out of the water too long—would it be necessary, perhaps, to wet them from time to time?

At the very least, he owed it to his sundered nation to find out.

Williamson returned to his desk, took a bottle of brandy down from its rack and poured two glasses, carrying one of these to Daniel. The slave, perhaps smelling it, opened his eyes.

“Daniel. If this all pans out, I’ll make you a free man. And I think your great-grandchildren will find America much improved.”

The Negro nodded, favored him with a hint of a smile, and took the glass.

The Captain boiled more of his tainted liquor; the fumes spiraled up topside through the tubes, summoned winds that luffed out the sails and drove the ship faster than the best of those noisy, smoke-belching steamers. He pondered his plan, turning it over in his head.

The slave sat with his usual stillness, undisturbed by the pitching of the vessel, hands in his lap.

“Mr. Josiah?”

The Captain looked up. A shadow had fallen over Daniel’s face.

“I know why, sir. I know why they wanted that ship.”

“Why, Daniel?”

“Best get up top, fast.”

###

Williamson scrambled up to the sunlit weather deck. Crewmen were lined up along the port side, pointing. A patch of white water appeared there, as if stirred up from below. The Captain glanced around—two, six, a dozen or more patches of white, boiling all around the ship.

Merpeople, he thought, and gripped the bulwark.

As if summoned, they rose into view.

In spite of himself, Williamson jolted, cursed himself silently for it. These were not the otter-playful humanoids sighted by Columbus and countless whalers. They opened their mouths and shrieked, sounding like a choir suddenly fallen into hell.

And they wore armor.

They wore helms with noseguards, breastplates and gauntlets, gorgets at their throats. Their arms were shielded; the tops of their webbed feet were shielded. Their sailfish-arm fins protruded through slits in the metal, and the cuffs jutted over their hands to taper off into twin blades—did they get that idea from the Virginia’s forward ram?

Williamson leaned over and stared. The knights of old wore between forty and sixty pounds of plate metal and had to stay out of water more than head deep, yet these creatures, they can swim right to the surface with seemingly no effort . . .

Scraping sounds from below. Williamson leaned out and saw mermen hoisting themselves up from the sea, streaming water that sparkled in the sun. They stabbed the wooden hull with their gauntlet blades, right and left, climbing end over end. In three seconds Williamson found himself face-to-face with a towering merman, easily seven feet tall, perched with catlike balance on the gunwale, dripping water.

The Captain spoke a single word. The merman fell backwards, thrown as if by a catapult, and hit the water with a splash like a cannonball. Even so it did not lose its grace, but twisted around in time to plunge in feet-first. In no time it would scramble up the side again.

“Men, get below.” Crewmen scrambled to comply.

Two more intruders sprang over the sides. Williamson spoke another phrase and they went rigid. If he only had time to boil up the specific fumes and breathe them in . . .

He clattered down the ladder, burst into his cabin.

Daniel was standing, in a sweat now. “Mr. Josiah . . .”

“Not your fault.” Williamson flew to the liquor rack, grabbed a bottle, then another. He threw one to the deck and smashed it. Something like wisps of steam curled up from the stained deck and shattered glass. The other bottle he uncorked.

Footsteps outside the door, striking the deck together, like men marching.

“Daniel, open the door.”

The slave did so. Four armored mermen crowded the passageway. Williamson swung the bottle, splashing its contents on the leading attacker. The merman stumbled and fell to the deck. The rest appeared to relax.

Williamson, eyes fixed on the intruders, pointed backward. “Daniel. On the rack is a bottle marked 1792, with a picture of a smiling sun. Empty it into a beaker and heat up the stove. The more fumes we get, the better.”

Without waiting for a reply, he shut the door and hurried up the passageway past the mermen. They turned and followed, still stepping in perfect unison, metal clanking with every footfall. Were they directed, perhaps, by a single mind, like ants or bees? If so, where was their “queen?”

He passed a number of crewmen who gaped at the sight of his captives.

“Johnson, Brown, follow me. We’re chaining these in the hold. Daniel’s cooking up a hex for most of the others.” The crew, armed with carbines, pistols and cutlasses, could fight off the rest. Guns were popping up topside.

Blue-green water burst through the starboard bulkhead, salty drops spattering Williamson’s face. A merman, then another, swept in with the torrent. Williamson stiffened. They had chiseled through the hull like sappers, and now, besides boarders, the Copernicus was taking on water.

One of the intruders let out a shriek and rendered a precise swipe of its arm-fin. The Captain leaned back out of its path. He spoke, then shouted, his captives thrown into disarray, clanking and splashing to the deck and struggling there as if losing all sense of balance. Another newcomer, then another, rode the white torrent in. Water swirled around Williamson’s ankles.

“Everyone off the ship,” he called out. “Pass the word.”

Another explosion of water aft. Water streamed around his feet, soaked through his shoes, his feet icy cold. Would Daniel get out in time?

The mermen stilled, seeing, or sensing, that the contest was over. They looked at Williamson with patient eyes.

He crinkled his brow, aware of the stirring in his head, the thoughts not his own. He almost, but did not quite see, the eyes—enormous, bigger and whiter than any merman’s, below the surface where the sunlight did not penetrate. Its thoughts, synchronizing with his own. He saw America, and Confederate America, as they were now; he saw the guns and the burning ships; and he saw ironclads, new Monitors with double turrets, and the Southern rams. And new vessels after those, larger, sleeker, diving under the ocean like the whales. Exploring. Discovering. And then chasing, putting out vast nets . . .

So I was only the first to get this idea. Like Daniel, the merpeople also had a talent. No, not like Daniel’s…how far ahead could they see? How far was Williamson seeing?

He shivered; the icy water had reached his knees. The Copernicus did not list or tilt. She was settling all at once, level, into the Atlantic–with such precision they must have gouged every breach! The mermen seemed not to notice the rising tide. They were equally at home in both elements. The water rose to Williamson’s waist, the cold gripping him. He forced his teeth not to chatter. Would they simply let him drown? Or finish him off themselves?

Shaking off the thoughts, he sloshed back aft. No one followed. Without a ship, he was no longer a threat.

“Daniel?”

He found the slave topside. Daniel reached down the ladder and gave the Captain a hand up.

###

Williamson and top-hatted servant sat alone in a private sail launch. It rose and fell with the waves. He counted the lifeboats scattered around him, and the crewmen. Most had gotten away safely, at least.

The slave held up two bottles. One had an amber label, one green. “Managed to save these, Mr. Josiah. Hope they help.”

Maybe. In a minute he would read his tiny writing on the labels and see if they could summon a blockade runner bound from Bermuda or Cuba, or a Confederate privateer, or even a sidewheel steamer. Right now he needed to sort out the images haunting his mind: the luminous merpeople, the ones burning white and smoking under water, scorching off the two-inch-thick hull plates, reshaping the iron; fitting the helms and breastplates, gauntlets and helmets to every grown merman. They did this in days and all underwater?

But our troops have modern rifles. Artillery…

The mermen knew. They had long studied the land-bound warriors from afar, and laid their plans: the rivers that snaked through the South, the cities built on their banks. How much armor could they forge from the Virginia’s seven hundred and twenty-three tons of plating? What about the Union’s Monitor, France’s La Gloire and others?

By the time Williamson and crew arrived home, what would they find?

He wondered if, by then, even a sorcerer could make much of a difference.