Those Who Came After

Those Who Came After

by Jeffery Scott Sims

Sugar attracts flies, resulting in maggots, and if left untended and unprotected shortly reduces to seething vermin, its virtues first polluted, then annihilated. Must it be? In this specific case, undoubtedly, but may we derive from this simple, if disagreeable, observation, or others of its kind, a general principle holding for all things, and all of life, that the good draws to itself evil, and if undefended must fall prey to such? I would reject the notion, yet I can multiply the sorrowful instances, gather them from the anecdotes of individuals or the billowing sails of history to fashion a fearsome pile. The more lugubrious among us will declare, “Always it shall be so,” an assertion I may strain to refute with “Not so long as hope sustains,” while I endeavor to resist the heaping evidence of sinister entropy. I hesitate to accept the charge, for two reasons only which I postulate without for a moment expecting to convince others, perhaps not even myself: one, that I do not wish to believe it; two, that were it so I should suppose many more stories current of the grotesquely supernatural—of the sort I am about to relate.

I tell a tale of privately experienced horrors, yet this should be understood too as my narrowly personal remembrance of a house, an old white frame, single level structure, possibly unremarkable in its own right; not so much of how it was brought into existence or how it fared through the years, but rather how it came to an end. For the house is gone. It burned, the result of a sudden blaze that caught and spread and destroyed everything in mere minutes. The firemen, arriving with decent alacrity, had not a chance of saving it. Surely they tried with their customary proficiency, yet given what I learned beforehand, it is wise to allow for an element of doubt. They may have been glad to see it go.

What means this? Well, therein lies the tale, commencing now. I traveled to the beautiful city of Sedona across a vast distance of years and geography. Business, not sentiment, by unusual happenstance called me to Arizona, my home state, but that transaction complete, sentiment only retarded my flight back to my chosen life elsewhere, and with a few days at liberty dictated a return to the place of my birth. Never had I so much as paid a visit in all that time, with the consequence that as I drove up through the Verde Valley in the rented car I imagined finding the area unrecognizable.

Change arrived before me, of course, that unwelcome change often waiting patiently in the wings until one departs from a region. The city had sprawled dreadfully, in deplored if inevitable American style, gobbling up any conjoining territory not secured by the stout outposts of the surrounding national forest. Its commercial heart, having wholly surrendered to the tourist trade, presented nothing familiar to me. Were this all, my attenuated tributes to youth might have constituted a dream, but I speak of Sedona, Arizona’s jewel, and there is that more there which abides so long as does this age of the earth. The glorious mountains, the red rock spires and buttes, the majestic canyons lived on unchanged, and in gazing upon them again I felt the unaccustomed tug of home.

Therefore whatever else I would do (knowing me, most likely how quickly I would dash away) I must see, perhaps for a single and final time, the old home place. With the transformation of downtown avenues, both of routes and occasionally names, I suffered a minor ordeal in tracing a connection to Choccolocco Street, but when I did wend a path to the edge of the old neighborhood and the fizzled fragments of memory united with modern reality I experienced immediate surety, driving into firm and certain ground. I pulled into Choccolocco, a fine Indian name that meant nothing to the local Apaches, for the lane had been christened by Alabama settlers in the horse and buggy era; found that little had changed there since I last beheld it, and nothing vital. The little Thompson cottage sported two esthetically inappropriate, hopefully utilitarian extensions, while the Schuerman manor had been converted into a presumably necessary law office, and there were other indicators of the world’s turning, but it did seem for a brief spell as if I had transited in reverse the decades and come round again to that exact tick of the celestial clock when my life had stepped away.

Then I came to the house, number 204, at the corner of the little intersection across from the big Methodist church, pulled up short and stared. How the curse of time had trumped the kindness of memory! All the joys and cares of childhood collapsed into this black hole of dilapidation. The eyes of the boy looked with artless indifference upon a trim, clean, whitewashed abode adorned with green lawns and manicured rows of rose bushes, guarded by the ranks of picket fence and lofty sentinels of ancient oaks. The eyes of the man blinked in pained irritation (through a dull darkening of vision, I thought, an odd dimming of light, as from absent clouds or an unscheduled eclipse) at the pitiful evidences of neglect, the sullied oak slats, the peeling paint, missing roof tiles, withered grass, tottering shafts of leafless trees, most of all the desiccated carcasses of colorless shrubbery. The flowers had died. The entire tableau, to my antagonized imagination, reeked of death.

To such a state had fallen the cradle of my life. Yes, there had I been born and raised, and my sister, and my father and his sister, in the house purchased by my grandfather when he married. Come to this? The dwellings about did not exhibit these symptoms of disquieting decline. Something unique, then, happened here. So I had thought, too, of its past. My befuddlement, amazement, even anger, were stoked by serene recollections of mellow happiness. The urge to a task welled up within me: I would know more, must demand understanding of these squalid conditions. Decided on the spot, action followed. Arrangements made to extend my stay, I set to work.

I realize it is incumbent on me to get to the point, and that I will quickly enough, reporting on terrible things, yet a summary of the past, however apparently digressive, remains pertinent to my story, may indeed prove critical in so far as it relates to me, so attend to this précis on the life of the house in which once I lived. The Martins erected the basic structure in very much its final form in 1894, years before Phillip Miller’s daughter lent her name to the incorporated township of Sedona. At that time houses stood few and far between in that land of farms and ranches, with the community gradually growing in clumps atop the hills overlooking Oak Creek. By 1936, when my grandfather acquired the place, it already lay on a proper street—if unpaved in those days—with other houses around, and indoor plumbing too. Before the war the street received a coating of asphalt and the house, at “Pa Pa’s” expense, electricity.

Forgive the tedious details. Here is what really matters. By the time I came along generations of my folk had lived there, and they fared well, and they passed on that wellness to me. 204 Choccolocco did not constitute a paradise, nor would I outrage honesty with the absurd claim, but it was a genuinely, down deep, swear to God happy home, if for no other reason than that we all lived there at one time or another, thereby partaking in the benefits accruing from the sharing of space. Grandparents to children to grandchildren, these intricate combinations of hopes and dreams, all belonging there, bound despite their disparate qualities by the unity of the house. Collectively we infused its material essence with the goodness we generated, our dross leaving no permanent stains, for on the goodness we throve, and so after its fashion did the house.

There is something here, on which I can not quite put my finger, beyond subjectivity. What I have just told transcends my own assertions, for the other denizens of that place, my people, often spoke likewise. The atmosphere I describe continued after my father sallied from the house with his new family for far places, for his sister and her family moved in to continue the story on their, similar, terms. The tradition, however, ended with them too, for several years ago, having reached retirement, and desiring to be near their own wandered offspring, they sold the house to strangers, relocating themselves down by Phoenix. Thus a chapter closed, with a certain nostalgic regret perhaps, but with no hint, in any degree, of the manifestations of the morbid.

This much I knew as I pulled away in dismay from the old house, formulating my vague quest for additional enlightenment. I merely wanted to know what had gone wrong during the intervening fifteen years. One glance warned me that much of a fellness had occurred in the meantime, although the revelations to come might, as I mused then in generic prediction, have proven just sourly pedestrian. This conclusion, I discovered, would have sorely underestimated the awful nature of the domicile’s fate, which has everything to do with those who moved in afterward.

I speak not of the new owners who bought the house from my aunt and uncle, who never lived there themselves but rented it out, nor of the regular tenants who tried and failed to make lives there. To the best of my knowledge they were all upstanding citizens. I picked up a thing or two about them when I commenced my fact-finding campaign by studiously quizzing the neighbors, plainly identifying myself (none of the old folk who might have remembered me remained) and my concerns. From those dwelling round-about I received an earful. 204 was a bad house, bad in toto, unfit for habitation. Those who had not dwelt near long claimed it had always been a spooky place. With somewhat more precision, I learned from certain sources that tenants of the current owners came and went over the span of a decade, in each case shortly surrendering to what my informants would or could not exactly define, a pall or force rendering continued occupancy intolerable.

The most recent vacating of the property, already some years ago, seemed well on the way to assuming a peculiar finality, which datum led me to the current owners, a married couple of means, who graciously consented to an interview. Possibly they second-guessed themselves when confronted by my dubiously suggestive questions, including a mild harangue concerning the pathetic state of the grounds. Their voices tinged with “miff,” they declared that the pretty lawn and gardens (features favoring their purchase) had been the first things to spoil, nor had any amount of care, notwithstanding swelling expense, reversed the ugly trend.

My questions culminated in one most outré, guaranteed to irk and distress them. Whence had arisen, I queried, the widely held belief, mentioned to me by a number of locals, that the house was haunted? That bizarre claim, see, formed the keynote of commonality among the neighbors’ statements, one presented with as much earnest certitude as with unhelpful ambiguity. Having eagerly anticipated a clarifying answer, this pair’s equally murky response induced only annoyance on my part, adding virtually nothing to my store of contemporary lore. From their very first tenants, they averred, a consistent pattern took shape, woven of grievances and accusations. These, hurled against the landlords, denounced the house as hostile, oddly dark, plagued by disembodied whisperings and, if sporadic complaints be affirmed, shadowy visitations at awkward hours. Collating of grumbles and rumors produced a picture of a black house of terror, one so starkly delineated that it repelled its human inmates, climaxing in fearful and angry departures, until in due course it became impossible to further rent the place. Did any of these stories, I pressed, attempt to explain or provide an underlying logic to these inane mouthings? The owners, with recourse to the same vagary I had confronted earlier, expounded stray gossip of a tragic or suspicious death darkening the house’s history in a previous period, a hazy event dating prior to their less than lucrative acquisition.

I left them on that note, incensed by the spurious condemnation. Knowing the legitimate accounts of my family and before, I could quash the indictment “with prejudice,” eliminate it from consideration. Nothing of the kind had ever occurred there in the old days. Could it be that prosaic ugliness had reared soon after, or at any time thereafter? Consultation of public files elucidated, and disconfirmed, the likelihood.

My amateur but fervent research detained me for several days, at the end of which I realized I had gained no ascendency over morose ignorance. Stymied, the distastefulness of the affair overwhelmed me, so I chose to renounce the wretched business, and be about mine. It was not my house, after all, nor that of anyone for whom I cared. Nothing I accomplished, no data gleaned, could have any practical effect on my life. The more I brooded, the more forthright indifference struck me as the most scrupulous stand.

Intending to leave Sedona for good next morning, I went out for a late dinner that evening, headed back for my hotel after the town had closed down for the night. On impulse I detoured, took a spin down the old street—a few blocks deviation—in order to grant myself a swift, harmless glimpse, inspired by pangs of fond reminiscence of the halcyon, for that which yields to relentless time. I did stop there, grinding into the gravel driveway this time, to peer blankly through the windshield. A distant street lamp allowed me only enough radiance to discern fundamentals of form: the forlorn work shed to the right, the path into the back yard straight ahead, the bulk of 204 to my left. There, dimly seen, the double door giving onto the kitchen, one I had passed through a thousand times, during a life that seemed now an earlier, fading incarnation.

Then and there I might have closed the book, but another whim led me to climb out of the car, take those few steps across the years to those doors, reach out and jiggle the brass knob of the outer, screened door, as if I would turn it, open and enter into light and familial gaiety. Locked, naturally; the moment deflated, I made to leave, and then it began.

The first indication? The impression—subsonic sounds, vibrations in the still air, or that less palpable still—that something weighty and ponderous had rushed up against the far side of the inner door to press heavily against it. I drew back in haste, heart thumping, striving to laugh at imagination, yet feeling threatened there in the dark.

Slowly the screen door creaked open and outward, halting as it rapped wall. I should have reproached the wind with false invitation, only then the inner oaken door swung with a creak the other way, unmasking an oblong of darkness. I stood nailed to the spot, intent on that obscurant breach, pondering breathlessly. I had no right, knew beyond question (without yet perceiving the import of the question) that the house belonged to others, and a host of reasons bade me leave that place. I did manage to drag myself back to the car, all the while arguing inwardly for swift departure. Regardless, having with furious resolve fished from the glove box a handy pen light, I advanced once more on the gaping doorway, knowing it for the brink of mystery. Who beckoned? I accepted the presence of a presence, so to speak, yet assuming a position before that cavity disclosed nothing. Quite otherwise, I ascertained that the electric light did not penetrate past the jamb, therefore if I would see, I must cross over.

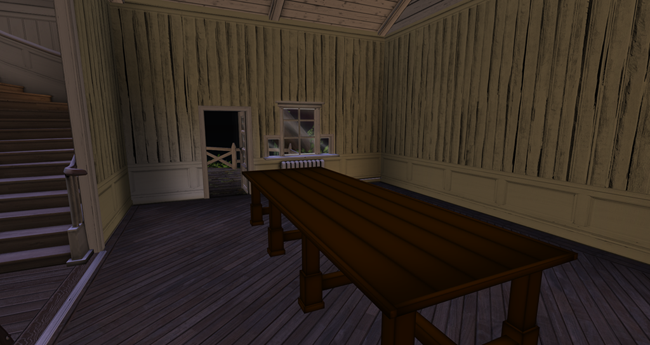

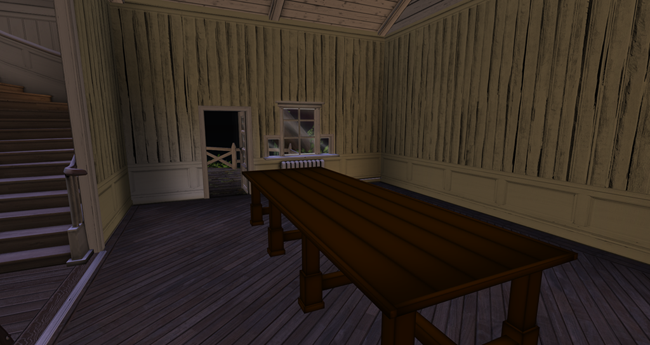

Stepping into the vestibule which once served as the breakfast nook, separating the kitchen from the den, I could then discern my surroundings: emptiness, caverns of rooms in which dust lay thick, divested of the props of life. Necessarily what I remembered, the simple table, that old comfortable sofa, the cluttered book shelves, had gone, maybe still with my people; as had gone whatever subsequent ephemera others had sought to plant in that fertile soil. The house was a shell, akin to a skeleton stripped of flesh, which I might analyze with my flash as would a medical doctor with the tools of his trade… only I realized that 204 continued to harbor an insidious species of animation.

It hit me when I entered, left me gasping. The presence further revealed itself as a force, a dark power that struck into my brain, that jolted my body with a real physical intensity. I conjectured a heavy gas, a dense miasma, a kind of clogging atmospheric syrup that suffused the air of the chamber; an ethereal gelatin composed of steeping rage, and contempt, and hate. It clung to all surfaces, damply pressed against my exposed skin, fouled my clothing. I shivered, cried out, made to back away, but something, doubtless with ill intent, bade me stay. Rejecting the offer, I nevertheless elected to advance after all, for the determination to proceed and learn conquered terror.

Terror it was, I knew as I passed through that room into the hall beyond that led toward what had been the bedrooms. Not terror as sensation, or response to stimuli, but embodied as a fiendish, hulking creature, a vast spider encompassing the house with its dangling black legs, glowering with many baleful eyes from the center of its filthy web. It, or they—yes, for I sensed a multitude, a pandemonium of cruel intelligence watching from all directions—had chosen to call me into their domain, to lay a trap, one baited with curiosity, meant to be sprung for my destruction.

In my prowl about this house that ought to have been readily familiar I detected unorthodox changes, alterations other than what could be imputed to architectural improvements, and which I deduced were warpings of space generated by those unseen others around me for amusement at my expense. The passage through the center of the structure bent oddly upon itself, as it had not and should not, while the walls at whiles leaned oddly, here convex, there concave, as could have been conceived by no professional renovator. At the far end of the corridor the ceiling dipped in a disconcerting incline that threatened by head. That change, I could swear, occurred as I watched, or between blinks, for I had not noticed it as I approached, which I should have, for it required awkward ducking.

In stepping forward onto the dusty floor planks of the master bedroom I actually leaned against buffeting waves of virulent, psychotic hatred that I feared would knock me off my feet. Dreading the thought of being brought low, helpless on the floor, to be smothered or drowned in the muck of horror, I braced myself, gritting teeth and clenching fists, the beam of the penlight swinging wildly, until I felt once more in control of my own being. Engaged in this battle, of singular and ultimate proportions, I strove to grasp the nature, the motives, of these remorseless foes.

The effort required no mental strain, for in their insidious, oblique fashion they told much in unheard whispers. These were the new tenants of the old house on Choccolocco Street, the permanent inhabitants, those who came after my folk abandoned 204 and left it vacant for those who now desired it. They had moved in to fill that vacuum, and having established rights of residency as the foulest of squatters chased out, through their subtle nastiness, the well-meaning interlopers who subsequently intruded. The place belonged to these creatures now—spirits, demons, effluvia of cursed spheres—nor would they brook intrusion from any being tinged with decency. Yet they invited me in; since I had come, they craved my indulgence, without immediately explaining why. I wrestled with conjectures. Merely to mock, for that they drew me into their lair?

In that room they opened up with their big guns, commenced what I realized was a war waged against my soul. Their methods advanced beyond hostile insinuation, disclosing mechanisms of haunting of a tangible quality. The ancient wooden floor of the biggest bedroom was porous, with slight cracks between the aged boarding and even a couple of small, hand cut holes, giving onto the crawlspace beneath, which may have served some obscure airing function in more primitive times. Now from them issued insects, or similar pests. Nothing, note, quite like normal spiders, or ants, or worms, but a squirming, writhing, slimy vomit of minute, phantasmagorical loathsomeness, all waving feelers, skittering legs, and bulbous stalked eyes. An army of tiny fugitives of nightmare oozed and scrabbled out of the woodwork, flowed across the dead boards, before I could react slopped onto my shoes. I confess to a scream, to a stupid kind of idiot’s dance, to an attempt to stomp the swarm to scarcely less revolting pulp. For naught my frantic defense, as the horrors existed only to sully sight. Ghosts of conjured or otherworldly vermin, they proved impervious to pistoning soles.

I fled that chamber of repugnance, slammed to the door behind me. In doing so I had entered the last major apartment of the house, the space formerly given over to the grand dining room. There I shrank from what I deemed a vision, though one not intrinsically repellent. Unlike the other rooms, mere cavities devoid of furnishings, this one possessed an item, one I was startled to recognize. The great dining table, polished oaken relic and centerpiece of countless family gatherings in the golden years, remained. Suspecting a trick, I dared stretch tentative fingers to it, felt genuine solidity. I had never known. To reasonably speculate, the table, too massive, too inconvenient to transport, had been left behind, perhaps an element in the real estate deal, for the benefit of future tenants. They had come and gone, those hapless ones, but the table survived.

As I rejoiced at this fragment of bygone sanity, the vise of cunning spiritual oppression screwed tighter, to a degree inducive of actual pain. The current occupants of the house, its true owners, the masters of this domicile, elected then to banish doubt, to strip the mystery from their crusade against my humanity. They crammed into my mind an excrement of knowledge, as much as material brain could hold, and I knew them then, if not for what they were—I leave that theme still to the wise men, to assert and dispute as they may—then for what they were doing there, and what they wanted.

However subjective my experience that night, I deem myself blessed (if that be appropriate word selection) with a profound, if chilling insight into the nature of the reality I share with my fellow men. I accept while rebelling against, as I must would a knife in the back, the fact of entities inhabiting our world or universe that exist only for the purpose of tarnishing, of despoiling all that is fine and uplifting in this cosmos. I claim no special wisdom as to their genesis or motivation, simply know that they are driven by a prime impetus to destroy the good. I think of them as a kind of sentient pollution, or more accurately a conscious corruption that thrives on the corpse of happiness. This house, my house, the house that had belonged to us all, had known joy woven into enduring memories… and then we surrendered it to them, and into it they swarmed, in their mad hatred of the good craving the total extirpation of what the house meant to us, what it had come to symbolize.

They asked me in this night (so they bragged, in wordless boasts my mind could hear) that they might complete their victory by forever poisoning my memories of the place. This they set out to do. As the room suddenly shuddered and shifted crazily about me they pounded into me false images, lying figments of times gone by intended to replace true recollection, fomented to render 204 distasteful, to convert it into a perpetual realm of the abhorrent. I knew them as lies, but felt with a rising gorge of revulsion the putrid fabrications slinking into my brain, endeavoring to supplant the virtuous reality with the sham of malicious invention. Had they truly the power to do that to me?

In despair I banged fists to the table, my flash hurtling and shattering, moaned a prayerful “No.” The table bucked, as if to throw me off. Slamming down open palms, there in that tortured darkness, I steadied the table’s weird heaving, cried “No, no, no! You can not deceive me, for I know the truth. What was will forever be. Never can you take it from me. It is mine, now and always, indestructible whatever you do, irrespective of the evil you devise. So long as I, so long as we remember, the good endures. You have failed!”

They shrieked in the lunacy of their obscenely feral enmity. Foolishly they lashed out, stupidly made their final odious play. On the instant an uncanny greenish flame sprang up from all corners of the room, flared up the walls and raced along the baseboards. Was this another vexatious pretense? No, by God, for I felt the mounting heat. If they could not debase the monument, they would obliterate it. Dashing out of there, I passed into corridors and chambers now utter mysteries to me, hopelessly twisted, all afire, pursued by the monstrous music of hideous screaming. Every door had closed, attempting to seal me in, but a determined shoulder, soon much bruised, opened each in a rush. One more door, like them all unknown, giving onto strange blazing scenes, and I plunged into the open air, not turning until I reached the car, to observe from there the spectacular smoking, crackling disintegration of the house at 204 Choccolocco.

Expediency bade me go, thus I went, nor did anyone think to pester me later, as they might have done. I suppose adequate insurance minimized the injury. I have since heard ought of consequence. That matters little, since I know the full story. Those who came after lost: the declaration sums the tale. Those infernal powers destroyed nothing by their spite, took away nothing as they withdrew in search of fresh exploits on this earth or, as I would like to believe, displaced to less comprehensible regions elsewhere, more congenial to their kind. I dare say they have miserable triumphs to their credit—sadly better I understand the machinations of this unfortunate world—but not this time. When in extremis I cried from the heart. I contended honestly, earnestly, and as it happens, accurately. The good endures, for those who love it; let that stand as the requiem for a house.

I am an author devoted to fantastic literature, living in Arizona, which forms the background for many of my tales. My recent publications include two volumes of short stories, _Science and Sorcery: A Collection of Alarming Tales_ and _Science and Sorcery II: More Tales of the Strange and the Fantastic_; a novel, _The Journey of Jacob Bleek_; and the short stories “The Kingdom of the Anasazi,” “The Mad One,” “The Ghouls of Kalkris,” “The Granite Dells Mystery,” “The Castle of Chakaron,” and “The Eye of Blug.”

I am an author devoted to fantastic literature, living in Arizona, which forms the background for many of my tales. My recent publications include two volumes of short stories, _Science and Sorcery: A Collection of Alarming Tales_ and _Science and Sorcery II: More Tales of the Strange and the Fantastic_; a novel, _The Journey of Jacob Bleek_; and the short stories “The Kingdom of the Anasazi,” “The Mad One,” “The Ghouls of Kalkris,” “The Granite Dells Mystery,” “The Castle of Chakaron,” and “The Eye of Blug.”

http://jefferyscottsims.webs.com/index.html