A Choir of Demons

A Choir of Demons

by

Anthony Francis

“Perhaps you hoped for peace and quiet on your first assignment out of Academy,” barked Lord Bharat to his newest charge, a freshly minted Lieutenant in the Victoriana Defense League. “But Expeditionaries fight monsters—and here you will have your mettle tested!”

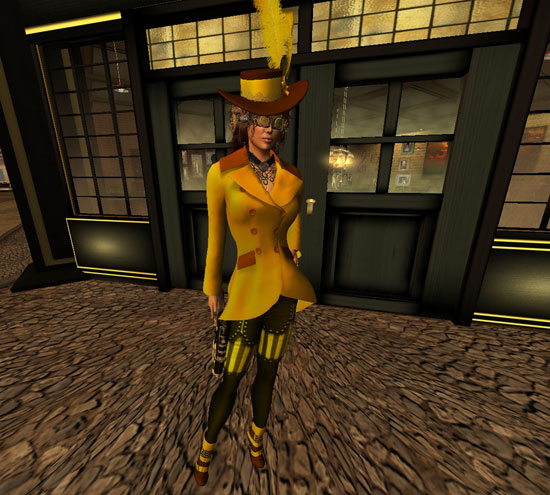

Lieutenant Jeremiah Willstone stood ramrod straight in her new gold tailcoat before her newer superior—then smiled and put a hand on her hip. “Either Navid didn’t send you my file, or you’re taking quite the piss, sir—ah, the latter. Well done. I do admit, you had me going—”

“Forgive a little hazing—of course I’ve read your file,” Lord Bharat said, chuckling, sitting on the edge of his desk, extending his hand to the open folder beside him. “I’d wager you tackled more Foreign Incursions in Academy than most of my agents have in the field.”

“Well, sir, I wouldn’t know about that,” Jeremiah replied: her mentor, Dean Navid Singhal had warned her about Bharat’s peculiar sense of humor. “I feel lucky to be here. I’m given to understand there’s no better place to fight monsters on the Eastern Seaboard.”

“A fact itself worthy of investigation, another time,” Lord Bharat said, eyes glinting. “Make no mistake, Lieutenant: Boston’s Eyrie is the VDL’s premiere forge of Expeditionaries. We will train you well. But given your track record, I rather think we’re lucky to have you.”

“Well,” Jeremiah said, coloring a bit; Navid had promised her a good recommendation, which in turn had won her an excellent post back in her home town; but perhaps he’d talked her up a mite too much. She returned to attention. “I’ve been lucky, sir: right place, right time.”

“Humility is a virtue,” Lord Bharat admitted. “You struck the nail square, Lieutenant: right place, right time. You were lucky, or unlucky, to get caught in the thick of an Incursion, but even we don’t know where the monsters will strike next. Much of our work is, I hate to say—”

“Grunt work, sir?” Jeremiah asked. Navid had warned her she would have to prove herself—and had outlined the kind of work a junior Expeditionary might be called upon to do when not fighting monsters. “Investigate, collate, report? I am prepared to serve, sir—”

Two raps sounded, and Bharat’s efficient secretary entered, politely interrupted, and handed Bharat a dispatch. While her new superiors muttered, Jeremiah stood at attention, expecting to be dismissed at any moment—but then Bharat looked at her thoughtfully.

“Well, Lieutenant,” he said, handing the dispatch to her. “Looks like your bailiwick.”

“A … police matter, sir?” Jeremiah said, her voice unexpectedly rising; most unbecoming in a soldier, but she hadn’t expected to be sent on a formal mission on her very first day. Navid clearly had talked her up too much! “With respect, sir, I’ve not even completed orientation—”

“You’re wearing the tailcoat,” Lord Bharat said firmly. “Aquit it well. Dismissed.”

Jeremiah clicked her heels, whirled and marched off, her head positively spinning. What were the protocols? Who were the players? She was going in blind! She tried to pump the dispatcher for details, but he sternly sent her on her way: the plea was urgent.

And so, within the hour, Jeremiah found herself halfway across Boston standing beside a detective policeman opening the bloodied front door of an artisan’s shop. Even as the hardbitten woman’s shaking hand cranked the passkey, Jeremiah steeled herself.

“Not sure whether this is an Incursion,” the detective muttered, “but it sure as hell looks like Expeditionary business.” The lockpick engaged, and the spattered door swung open with an ominous creak … revealing a dark red arc on the floorboards. “We left it just as it was.”

“Oh, you didn’t have to,” Jeremiah whispered.

Within the brassworker’s shop, the artisan sat sprawled in his work chair, head lolled back, staring at the ceiling, eyes wide open in terror, dried blood running from his ears. Up and down his whole body—indeed, over much of the shop—were carved rough pentagrams.

“Bloody hell,” Jeremiah said.

“My thoughts exactly,” the detective said, walking inside.

Jeremiah followed cautiously, noting the detective deliberately stepped forward onto a long, narrow strip of carpet broken into glossy, hexagonal tiles … with not a trace of blood on it. Jeremiah mimed the detective’s long step, asking, “What’s this track?”

“Forensic weave—you don’t know?” the detective asked. “Securing access is the first step in crime scene analysis. How could you not know, and be on the investigative detail?”

“It’s, ah,” Jeremiah began, “my first week—”

“And it’s Monday, so … your first day? Jesus God,” the detective snapped. “Monsters on the loose and the Eyrie sends me a rookie—”

“Oi! I thwarted more Incursions in Academy than most agents in the field,” Jeremiah replied, face flushing: from Lord Bharat, that was high praise, but from her, it was ridiculous puffery. Rattled by the detective’s cool stare, Jeremiah asked: “Were … there witnesses?”

“Not to the crime, but the resident neighbors,” the detective said, gesturing out the front window at the second-storey flats stacked atop the shops across the street, “claimed they heard what sounded like a choir of screaming cats … followed by the real screaming.”

“I can imagine why,” Jeremiah said, swallowing. Other than the blood, the ears looked whole … but pentagrams were cut all the way up to the poor chap’s neck, and the rest of the head looked like it had been pecked by a thousand crows. “Why’d you lockpick the door?”

“Key’s missing,” the detective said nonchalantly.

Jeremiah’s head swiveled to the detective. “Missing?”

The detective turned to look at her, then smiled grimly.

“So, the young miss has brains,” she said. “As well as a stomach.”

“The Eyrie wasn’t insulting you by sending a rookie,” Jeremiah said, standing, head whirling as she took in details of the battered shop. “They’re testing me. I may be their most junior Expeditionary, but I did actually thwart several Incursions in Academy—”

“So what does this tell you?” the detective asked, nodding at the corpse.

“Nothing about whether we have an Incursion,” Jeremiah said. “Foreign technology could have done this, but that’s suggestive, not conclusive. The pentagram symbology suggests the opposite—but again, simply consistent with a human source, not necessarily caused by it.”

“And the lacerations?”

“Stab marks, not bites or claws,” Jeremiah said, feeling like she stood for an Academy oral. “Could be a weapon, but more likely an assault by something Mechanical. He looks like he’s been swarmed by something. But his ears are strangely undamaged.”

“He’s bled out of them,” the detective snapped.

“But the outer ears, the pinnae, are untouched,” Jeremiah said, gesturing at them, then the well-scored cheeks, and the detective’s mouth opened. Jeremiah capitalized on the opening, waving at the ruined shop. “Your turn, ma’am. What does all this wreckage tell you?”

“Well,” the detective drawled, surveying the shop, the misshapen pentagrams carved over seemingly every widget and cylinder on its high shelves, and the scarred surface of the expensive brass autowhittler, “never seen anything quite like this, but … it sure as hell wasn’t a robbery.”

Now Jeremiah’s mouth opened.

“It surely wasn’t,” she said. “So … have there been any similar assaults?”

“Oh, have there,” the detective said, pulling out her notebook. “Closer to identical.”

#

In Back Bay Hospital, the detective confronted Jeremiah with an even more gruesome scene: a victim far more mutilated—not just ears, but eyes and even teeth gone—yet, chillingly, left still alive after her wounds, and even conscious, if delirious, when she arrived.

“Are you sure we can’t question her?” the detective asked.

“I’d like to get the blackguards who did this as much as you, but she can’t hear you,” the doctor snapped. “We need to rebuild her eyes, ears, part of the mouth—and she’ll have a long recuperation. She’s cogent enough to communicate, but we have no way to ask a question—”

“Maybe we do,” Jeremiah said, gently taking the woman’s hand, squeezing it, and lifting up her sleeve. A spidery network, not quite scars, not quite burns, climbed her arm. “These scars give me an idea. Was a cane in the victim’s effects?”

“Yes,” the detective said. “You think those marks were left by her attacker?”

“No, by her service,” Jeremiah said. “Lichtenburg marks—this woman’s a veteran.”

“Ah, of course,” the doctor said, touching his forehead. “Lightning burns, the cane—it’s keuranopolio, nerve damage from early thermionic blasters. Yes, her age is about right—”

Jeremiah began drumming on the woman’s arm: tap-tap-tap, press-press-press, tap-tap-tap—and the woman groaned, turning her bandaged eyes towards Jeremiah, the dark hole of victim’s mouth opening and saying, “Ess … ohh … ess …”

“You’re sending her a distress call?” the doctor asked, shocked.

“Just trying to hail,” Jeremiah said, “but yes, I’m the one that needs her help.”

After a halting back-and-forth refresher in Morse, Jeremiah was soon asking meaningful questions and getting slurred yet comprehensible answers. The victim knew little: she’d heard a late night noise in her second-storey flat, descended to investigate—and had been swarmed.

“Like a choir of demons,” she moaned. “Dozens, hundreds. All over the shop, singing, singing. Saw me, swarmed me, cut me—made me listen to their song. Tried to fight them off … but they took my eyes. Ruined my ears and took my eyes—”

“Tell her she’s going to have a full recovery,” the doctor urged, and Jeremiah complied. For half an hour, she served as an intermediary between physicians and victim until another veteran arrived to translate; then she joined the detective in the hospital’s aerograph room, casually reading off the source and destination numbers of the call with practiced ease.

“Conferring with headquarters?” Jeremiah asked.

“How can I tell through this muddled glass?” the detective snapped, leaning back from the aerograph’s dial. “Bloody Boolean toys! They slice faces up like bread, and make voices sound like a Mechanical’s. Give me an old-fashioned analogue spectroscope, any day—”

“Agreed,” Jeremiah said, “but in the field, you can’t beat an aerograph’s range.”

The detective looked at her. “I thought it all crazy. Monsters from the skies, laying waste to Surrey, conquering Iceland. But it’s all true, isn’t it?” When Jeremiah nodded, the detective shuddered. “And you. Diploma still wet, but more Incursions thwarted than a field agent?”

Jeremiah felt embarrassed. “Right place, wrong time,” she admitted. “I did my duty—”

“Do it now,” the detective said. “You’ve real experience. You’ve seen real monsters?”

“All there are to see,” Jeremiah said quietly. “More often, we face their technology—”

“So use your judgment,” the detective said. “You believe that talk … of demons?”

“I don’t know yet,” Jeremiah said. “Best to be cautious, dealing with Foreigners—”

“Not what I meant,” the detective said. “Could it literally be a choir of demons?”

The question chased Jeremiah all the way back to Beacon Hill, especially as the seasoned detective’s question sank home: if the Earth could be attacked from the former purity of the open skies, perhaps it could be invaded on other fronts as well … invasions from parts far darker.

Demons sounded preposterous, but her mentor, Navid, had warned her not to reject any idea as a matter of course, but to instead seek evidence … which was no aid to her darkening mood, with the sole survivor raving about singing monsters that destroyed ears and eyes.

It didn’t help that as a newcomer to the Eyrie, her desk wasn’t in the airy glass tower, but in the dungeons of the Hill, crammed dark and deep within the sub-sub-sub-basements of that hollowed out mountain, in that lower layer some Expeditionaries called “hell itself.”

After winding through dripping tunnels, Jeremiah finally found the cozy swastika-shaped desk she was to share with three other junior Expeditionaries. Racing time, she punched up her report, handed the collation card to the dispatcher, then headed to her first night class.

While new Expeditionaries were expected to serve a two-year tour out of Academy, Jeremiah had been tracked into an accelerated programme designed to turn her into a field agent as soon as possible. Under Bharat’s guidance and with Navid’s blessing, she’d work two shifts for the next two years, following the normal rotation during the day, but at night cramming in everything from the intricacies of airships to the subtleties of infiltration.

It might be six weeks, or more, before Jeremiah would have time to visit her aunts and uncle out on the family farm in the hill country, and even then probably only for a day pass—but, with luck, she’d find her niche and get a proper posting within eighteen months.

“Outfitting,” the instructor said, waving his hands over the varied equipment of a field kit, “is the foundation of Expeditionary work. Thanks to modern shape readers and auto whittling, we can customize each Expeditionary’s gear to their individual bodies—”

Unaccountably, Jeremiah found the lecture boring, perhaps because she’d interned in Mechanical Sciences in Academy and so knew the subject too well—or perhaps because she’d already learned truly experienced field agents found their own artisans and self-equipped.

But, she dutifilly and skillfully measured her hand and weapon as instructed, rolling off a wax cylinder whose jagged helical groove held an encoded song that would instruct the whittler to sculpt a new pistol grip customized to fit both her left Kathodenstrahl—and her.

Jeremiah inspected the groove carefully: do a good enough job, and the instructor would add the squiggles that told the cylinder to copy itself, yielding her a shiny new brass cylinder she could use for years to come to print new pistol grips, even if she found her own artisan.

Artisans. Jeremiah shuddered, thinking of the poor soul in that shop—from the stock on his shelves, he’d been a craftsman. But students were quickly queuing up, so, holding her wax cylinder, Jeremiah stepped up to the whittler line, staring up at the massive brass machine.

Could it really be a choir of demons? she wondered. That sounded mad, but so did monsters from the sky. What would demons want with an artisan, anyway? The victims were unrelated, so it was unlikely revenge. And nothing was taken, so it wasn’t theft—

“Lieutenant Willstone,” the instructor snapped. “Your cylinder, please.”

Jeremiah stood before the instructor and the tall brass autowhittling machine, frozen. The machine was easily three meters tall and had to weigh close to two metric tons. Abruptly she shoved the wax cylinder into his hands and drew her Kathodenstrahl thermionic pistols.

“It will have to wait,” she said, checking their charge. “I’ll need canisters for these.”

“What—” the instructor spluttered, as Jeremiah seized his brown leather satchel and unceremoniously dumped its contents onto its desk—quickly scooping Expeditionary equipment and machine tools back into it. He said, “What in God’s name are you doing, Lieutenant—”

“Striking while the iron is hot,” Jeremiah said, raising a springloaded watchjiggler and inspecting its tines; with it, she wagered she could beat even the detective’s performance at lockpicking. “Lieutenant Philips, your notebook and pen. Ensign Adler, you’re my courier.”

Pen and paper in hand, she quickly wrote while she explained today’s case.

“Nothing was stolen, but access was gained,” she said, pointing at the whittler. “What that machine can make is more valuable than anything on those shelves—but an autowhittler’s the opposite of portable. I’ll wager some miscreant sent a tainted cylinder—”

“And had the artisans build a lethal commission?” the instructor said, angered.

“Begging your pardon, Lieutenant,” Adler said. “Isn’t it a matter for the police—”

Jeremiah ripped off a sheet and handed it to her. “The detective’s precinct and personal aerograph numbers,” she said, unbuttoning her tailcoat. “With full instructions, but there were five shops, and one of the break-ins happened after the victim was already in the hospital.”

“The break-in happened after the attack?” Philips asked, helping her slip on a Faraday vest—not fitted as well as a veteran Expeditionary’s custom kit, but the black metal mesh would keep her on her feet if she was hit by a blaster. “Ah—someone’s still using the machines!”

“And you mean to stop them by all by yourself?” the instructor asked, even as he replaced the canisters on her pistols and checked their sights. He held the pistols up. “With all due respect to your fearsome reputation, Lieutenant, you should not do this alone—”

“Who said I’m doing this alone?” she asked, slipping her coat on, then taking her pistols. “You’re all Expeditionaries, ladies and gentlemen: time to serve! You lot take the nearest shop, I’ll take the next one. The other three are near the police station. If, together, we hit all five—”

“We have the highest probability of catching something in the act,” the instructor said. “And if not, this is a hell of a wild goose chase to start off the quarter with—no. Let’s call this a drill. Alright, you lot, gear up—and as for you, Lieutenant, take my autocycle.”

Ten bone-jarring minutes later, Jeremiah juddered to a stop on the cobblestone street beside the shop she’d started at, and immediately found her suspicions confirmed. Outside, the detective had agreed to post a Mechanical … but the metal man was marred and decapitated.

Jeremiah hopped off the canister-powered bicycle as crashes, flashes—and intermittent whines, almost like a chorus of dentist’s drills—emanated from the closed shop. Yet there was no external sign of forced entry; as she’d expected, the blackguard had used the key.

Carefully she drew closer—then something skittered inside the thick windowpanes.

“Blood of the Queen,” Jeremiah muttered. If the dispatcher followed the instructions she’d left, all Jeremiah had to do was not aerograph an all-clear within the next ten minutes, and help would be on its way. But beyond the skittering forms, a dark shape lurked in the shop, almost like a man in a cloak—and the whittler was spinning down. There was no guarantee the villain would still be here—and she had him now! “Oh well, who wants to live forever?”

Jeremiah drew her Kathodentrahls and kicked open the door, unleashing both blasters into the back of the dark figure as a horde of screaming metal forms spidered out of the way. The figure cried out as green thermionic fire spread out over his duster, but spun—unloading a blaster of his own straight into Jeremiah’s Faraday vest … where the aetheric fire similarly dissipated.

“Oh, bollocks,” Jeremiah and her foe said simultaneously.

Immediately Jeremiah threw up her left arm, shielding her face with her well-armored Expeditionary tailcoat; her foe pulled down his dark hat, which she could now see also had a Faraday weave. They circled each other warily, Jeremiah’s foe flanked by spidery forms.

“Self-replicating Mechanicals,” Jeremiah said, as the whittler disgorged a spider-thing moving ungainly on five bladed limbs—and carrying a lined cylinder. “Quite illegal—but untraceable if you used someone else’s whittler. Did you send tainted orders by post, or—”

“Had my little gremlins break in,” the figure said. Jeremiah caught a gleaming blue eye, framed by crow’s feet and perhaps grey whiskers, but it was hard to tell between the hat and the collar. “Don’t worry your pretty head about the details—you won’t remember them.”

He pointed at her and shouted a word of command—and the choir of demons skittered towards her. Jeremiah unloaded her weapons, but these springy monsters proved quite resistant to thermionic fire—and soon swarmed her, cutting pentagrams into her as they climbed.

“You might have a few nicks,” the choir leader shouted, as the awkward things climbing her began emitting ear-piercing screeches, “but no lasting damage other than addled memory. It’s a trick I stole from an Expeditionary: a frequency of sound that stuns the brain—”

“Doesn’t work,” Jeremiah cried, trying to bat the machines off and receiving more nicks and cuts for her trouble. “VDL scientists gave up our sonic stunner research long ago—any sound loud enough to stun the brain will also destroy the ears and stop the heart!”

The man hesitated only a moment. “I’ll soon find out if you’re lying!”

One of the whirring things crawled up onto her upraised arm, and Jeremiah stared at it in terrified fascination—then squeezed her eyes tight as it leapt onto her face. Despite the pain, she kept her eyes shut as the thing positioned itself on her left ear—and screamed.

The picture was clear to her now—suggestive, not conclusive, but she imagined an older man, an artisan for veteran Expeditionaries, getting desperate as his clientele aged out, turning to illegal commissions and desperate tricks to try to keep his dying business afloat.

But even as a second machine clamped onto her other ear and screeched, rattling her teeth with resonating harmonics, she realized the man used nonlethal weaponry—based on a rubbish theory, admittedly, but nonlethal, which was why the lacerations stopped around the ears. His blade-tipped crawlers weren’t actually trying to kill those unlucky enough to be at the wrong place at the wrong time; they just cut as they climbed on those five ill-designed springy legs.

But four of five victims had died, often mutilated to death as the demons clumsily tried to gain purchase to deliver their stunning sounds for maximum advantage. Those sounds seemed to recede even as Jeremiah grew dizzier, and from the warm wet flow in her ears she realized her eardrums had been destroyed. Bizarrely, she recalled a professor rattling off dismissive figures about sonics: “deafness in under a minute, brain damage within five, cardiac arrest within ten.”

Even with all her precautions, she’d be dead before help arrived.

Jeremiah flailed, then winced as the demons tightened their grip on her head—but an old friend, mortal fear, gripped her more tightly. She could not run; the choir had her legs. She could not fight; the demons swarmed her body. And from the eyes of the victim in hospital, she knew these Mechanical monsters were programmed to fight back if their victims even resisted.

Programmed. Jeremiah forced herself to recall that the monsters weren’t demons; they were, fundamentally, Mechanicals, and as another creature climbed onto her arm, she carefully opened her eyes and studied it, studied it and the whittler beyond.

At the core of the spiky thing biting into her forearm was a whirling brass cylinder. Like the rest of the monster, the cylinder which held the demon’s thought-song had been made in that whittler, at the behest of a song in an identical cylinder—but that cylinder’s song couldn’t hold a copy of itself within itself. No, it told the whittler to read and copy the complete cylinder using the whittler’s own programs, an unmodified whittler so it was untraceable … and as another monster rolled out of the brass machine, she saw how to use that.

Dizzy, swaying, about to lose consciousness—but all the time, staring carefully at the thing perched on her arm, ready to spring—she fumbled with her right hand at the one on her right ear. It twitched, but since she did not try to dislodge it, it did not fight back.

Her fingers found what she wanted, and threw the switch. The thing fell away from her right ear—and Jeremiah flinched and closed her eyes as the thing on her arm leapt in to take its place. Well, fine, she knew it would not be that easy—and reached up to fumble again.

The one on her right fell away, then the one on the left, each time another Mechanical demon climbing into its place, each one in turn falling as Jeremiah’s hands carefully reached up, felt over their mechanisms … and found the target she looked for.

Because before becoming an Expeditionary, she’d been in Academy, and had interned at the Mechanical Assembly Building, learning on the first day that the one thing found on every legally built and properly printed Mechanical … was a kill switch.

The demons were legion, but finite; and as the last two whirred to a stop she felt but could not hear, Jeremiah clamped her hands on them, fixed her eyes on the stunned man, and threw the demons at him, the first knocking aside his blaster—the second, his hat.

While he spluttered, knelt and rummaged for his gun, Jeremiah retrieved her own.

“I can’t hear a word, sir,” she said, taking aim, “but hear this: you’re under arrest.”

Later at hospital, Jeremiah relaxed in a dreamy haze while the fine manipulators of Mechanical surgeons cored her ears, rejuvenated their cochleal cells, restocked their fluids, and reknitted her eardrums. Tiny ceramics replaced destroyed bones, a notch better than original.

Still, sound came back slowly—muffled, distant, like Jeremiah was slowly rising from the bottom of a pool. It was hours later, recuperating from the anaesthetics the surgeons used while closing her cuts, that she caught her first words—from her outfitting instructor.

“… was neither a demon nor a monster, just a man—”

“That man was enough of a monster,” the detective replied, her voice both deadened and painfully distorted. “Seven dead we know of, and counting, all lost to some mad plan to undercut the competition by using their machines to manufacture his commissions for free! If the young miss hadn’t acted so quickly, and comprehensively, we would likely have missed him—”

“You struck the nail square, detective,” a familiar voice said, and Jeremiah realized her room was crowded with Expeditionaries, policemen—and Lord Bharat himself, standing gravely at the end of the bed, her dispatches in his hand. “Comprehensive is right—ah. Lieutenant. Welcome back from the Stygian shores. I believe I owe you an apology.”

“S-sir?” Jeremiah whispered, her throat dry. “For what, sir?”

“For disregarding your objections,” Lord Bharat said. “You aquitted your tailcoat well, but you were right from the start: there was no need to throw you off the deep end before you’d completed your training. As the detective has pointed out, a more senior Expeditionary could have been easily assigned to guide you.”

Jeremiah’s mouth quirked. “Would … would have just slowed me down.”

“Those were my thoughts exactly,” Bharat said with a slight smile, “but that’s because I was so focused on Navid’s recommendation of you as an operative that I forgot he also said you have the instincts of a commander.” He raised the dispatches, a glint in his eye. “Comprehensive is right: of course, there was always a chance you were on a wild goose chase, but had there been anything to find at all … I am unable to see how the your protocols could have failed.”

Jeremiah felt her heart lift, but the instructor said, “Could have gotten her killed—”

“Always a risk,” Lord Bharat said gravely, “but not without raising a clear alarm—”

“What are you all doing in here?” the doctor barked. “The young miss needs quiet!”

“That I do,” Jeremiah said weakly. “And Blood of the Queen, I’ll have it now, please—”

“Ah, she’s woken,” the doctor said. After a perfunctory examination, he pronounced her on the mend. “You’re lucky you stopped that blackguard when you did—you should have a full recovery. But to heal, you’re going to need quiet—real quiet—or you’ll develop tinnitus!”

“Oh, we wouldn’t want that,” Jeremiah said, ears ringing with his words.

“I’m sorry, I must order that the Expeditionary be given time off,” the doctor snapped, whirling on Lord Bharat, who merely raised an eyebrow. “Uh, she has lacerations, concussion, and as I said, a severe risk of tinnitus if the grafts aren’t given time to heal—sir.”

Lord Bharat opened his mouth to speak, but two raps sounded, and Bharat’s efficient secretary politely slipped past the doctor and quietly handed Bharat a package. Bharat smiled, nodded, then handed the sheaf of her dispatches to his secretary.

“Copy these to the watch captains with an explanation of their context—not as orders, but as an example,” Lord Bharat said quietly. He turned to Jeremiah. “As for you, Lieutenant, I have just the thing, the latest thing, especially for lovers of music—”

“Oh, God,” Jeremiah said. “With respect, sir, I’ve had all the music I can take—”

“Oh, I know,” Lord Bharat said, smiling, raising a contraption which looked like a large pair of brass earmuffs—with the addition of curious ear trumpets on their outsides, and thick rubber padding on their insides. “But these earpieces actively cancel all other sounds.”

Jeremiah stared at them for a moment, then took them gratefully. And on her six-week convalescence, out on the family farm in the hill country, despite the turning of the water wheel and the lowing of the cows, she read calmly … in complete peace and quiet.

By day, Anthony Francis programs search engines and emotional robots; by night, he writes science fiction and draws comic books. He’s best known for his Skindancer urban fantasy series, starting with the 2011 EPICeBook award winning Frost Moon and its sequels Blood Rock and Liquid Fire, all set in Atlanta and starring magical tattoo artist Dakota Frost.

Jeremiah Willstone first appeared in the short story “Steampunk Fairy Chick” in the UnCONventional anthology, and will next appear in Anthony’s forthcoming novel Jeremiah Willstone and the Clockwork Time Machine. She also appears in the stories “The Hour of the Wolf” and “The Time of Ghosts” in Twelve Hours Later and “Fall of the Falcon” and “Rise of the Dragonfly” in Thirty Days Later.

Anthony was co-editor of the anthology Doorways to Extra Time and is a co-founder of Thinking Ink Press. He’s co-author, with Nathan Vargas, of the 24 Hour Comic Day Survival Guide, and has participated in 24HCD successfully five times — and National Novel Writing Month successfully 15 times.

When not creating alternate worlds, Anthony’s research in artificial intelligence explores memory and emotion, work documented on the Google Research blog as “Maybe Your Computer Just Needs a Hug.” He’s also written about AI and Star Trek in an article in Star Trek Psychology. Anthony lives in San Jose with his wife and cats, but his heart will always belong in Atlanta.

To follow Dakota Frost, visit facebook.com/dakotafrost or dakotafrost.com; to follow Jeremiah Willstone, visit facebook.com/jeremiahwillstone; to follow Anthony visit his blog dresan.com, and to find Anthony’s books visit his Amazon author page or inquire wherever fine books are sold.