Mississippi Mermen

Mississippi Mermen

by Douglas Kolacki

Summer 1862

Corporal Leo Arbington stood at the bow of Picket Boat Number One, watching the stars come out over the Mississippi and listening to his brother Billy’s chatter.

“Relax, everyone! If you just heard that splash, it wasn’t them, just a catfish or somethin’. Sea-creeps never make li’l splashes like that. When they attack for real, you know it! They shoot up like cannonballs, white water explodin’ everywhere.”

Leo turned and scowled. Sweat trickled down the side of his face; the gathering darkness did little to dispel the heat. Ain’t there enough hot air already, Billy, without you blowing your own?

Lounging back against the port bulwark, Billy appeared at least a decade younger than the other men—his growth seemed to stop at age thirteen—yet the gaggle of butternut uniforms, farm clothes and blue sailor outfits drew closer to him as the light of day faded.

“And we can get’em, Billy?” a soldier in overalls asked. “We really can get’em?”

“I’m living proof, ain’t I?”

“Lemme see it,” another man breathed.

Leo turned his head and spat into the river. Tenth time today! Give the man a prize!

Billy pulled it from his pocket: a jagged metal shard slightly bigger than a Liberty-Seated silver dollar. “Plugged the thing right up close with the musket our Grandaddy used in the Revolutionary War—just ask Leo there, he’ll tell you! I was out huntin’ by the creek and there he was, armored like the Black Knight and still drippin’ wet, not five yards from me. Yeah, they got those sharp fins on their forearms and they ain’t scared to use’em, but I just told myself, Billy, now you be calm! And I raised Grandaddy’s old musket, it never failed him and I knew it wouldn’t fail me, but the bugger ran at me all the same. So I pulled the trigger, the old rifle kicked, and he flew back like someone yanked on his leash.

“I knew right then somethin’ big was up—somethin’ even bigger than our fight for in-de-pend-ence,” he brayed for the benefit of the Yanks on board—”and it was time to follow Leo into the Army—Lordy! how momma cried. Broke my heart, but a man’s gotta do his duty.”

“That so,” a sailor mumbled.

“You don’t believe me, look!” He pushed it at the mustached man’s face. The man wore a petty officer’s eagle badge on his sleeve and looked half-asleep in the dusk. “It broke off and landed right at my feet. That there’s actual platin’ from the Virginny!”

One of the Rebels snorted. “How do you know it ain’t from the Monitor or the Manassas?”

Or any warship? Leo examined his notched battle-ax. A naval weapon; he was accustomed to his musket. Hell, it could be just a piece of scrap from a blacksmith’s shop.

“They can be kilt, that’s what’s important!” Billy clenched his fist over his little prize and looked to his right. “Hey Daniel!”

By the stack admidships, a silhouetted figure stood perfectly still, a full head taller than anyone else even without his top hat.

“You found the Virginny, right?”

“Billy, quiet!” Leo hissed. “They’ll hear you all the way to the Gulf—”

“Yessuh, Massa Billy.” The deep voice rolled from the figure, and a faint nod of the head. “That I did.”

“Looky here—this piece a’iron. This was from that ship, wasn’t it?” Apparently he’d forgotten old Daniel was blind.

“It surely was, Massa Billy.”

“There, Leo!” Billy spun about in triumph, holding his piece high. “You see?”

“Not so loud if you please, Mr. Arbington.” Lieutenant Cushing, speaking at last—most of the time the bluebelly commander knew to keep quiet. Even the thirty-foot screw picket boat and the torpedo it carried came courtesy the United States Navy, along with six of its thirteen officers and men, but Arbington tried not to think of that. Everything had changed.

Another splash somewhere ahead.

Even Billy fell silent this time. Only the rippling of the eternal Mississippi and the song of cicadas from the bank, rising and falling in a steady chirring, sounded in the darkness.

Cushing checked and holstered his revolver. “Men, I hope everyone’s made ready.”

Metal rang softly as soldiers fixed bayonets. Those with axes took their positions at the bulwarks.

Billy had volunteered as a rifleman. He could do no less after broadcasting his story throughout his regiment and thrusting his iron trophy at everyone. Daniel, whose milk-white eyes were dead but saw things no one else did, informed Richmond that the sea-creeps had a queen, like bees and ants. She—rather it—was moving quietly up the delta into Louisiana. He told them what to look for: a mound-like object in the middle of the water with a “crawly” appearance, all but submerged, plowing against the current. Lookouts had sighted it below Fort St. Philip, then scouts further upstream.

Billy’s big mouth had done its job well: his commanding colonel summoned him to his tent, told him about the mission, and offered him this incredible opportunity to bring glory to the South. Leo, after swearing the air blue, hastened to volunteer as well.

###

The picket boat carried a fourteen-foot spar torpedo. Before setting out from New Orleans, someone who knew how to read and write brought a paint bucket and a brush, and covered the torpedo with messages dictated by the men:

Sea-Creeps Go Back To Hell!

Dixieland forever

Long live the South

Glory Hallelujah!

Billy coolly dictated his own: “‘This time it’s your leader, sea-creeps!’ And put my name on the end, real big-like, so they can’t miss it.”

Leo, leaning on his ax, rolled his eyes. “That ain’t never gonna fit, Billy, and it don’t matter anyway ’cause it’s gonna blow up. They ain’t gonna see it!”

Navigating the river, Leo knew he wouldn’t see the Louisiana, the Arkansas or any of the other iron juggernauts the Confederacy had built to compensate for lack of numbers. What was left of them, and the plating they’d been stripped of, lurked somewhere beneath the surface—here, or Chesapeake Bay, Mobile Bay, the James and Elizabeth and Potomac rivers, or any of the endless networks of waterways and bayous snaking through the country and especially the South. The Federals had been spooked enough to haul Lincoln out of Washington in a big hurry. Davis staunchly remained in Richmond, come what may.

The Virginia. Leo could still not quite believe that these mermen, or whatever they were, swarmed over that ironclad on her maiden voyage and dragged her out to sea. She weighed over four thousand tons! But everyone from Secretary Mallory on down swore it had happened, and now the sea-creeps were appearing, probing and attacking in spanking-new armor, and increasing as more ironclads disappeared. The preacher back home had said they were God’s judgment on America for this war; ministers further north tended to claim that the judgment had to do with slavery, and the sea-creeps were out to make slaves of their own.

Leo was certain only of two things: One, they were damned ugly, and two, he didn’t take too kindly to being forced to side with the Yanks.

Billy had started up again, at least keeping it down this time:

“—And so help me God I could see what that critter was thinkin,’ just like Daniel. Their leader was gonna come right up ol’ Miss—hell, I coulda told’em before Daniel did, and they wouldn’t have needed scouts to watch for it…”

The launch, motor puttering softly, rounded a bend to port. Leo leaned forward over the bow, squinting, but he could see too little; only the twinkling galaxies overhead and the cypresses crowding either bank, darkened now to black silhouettes. Everyone had hushed, but Billy rambled on, not seeming to notice, shut up Billy, shut up….

“Plain as—”

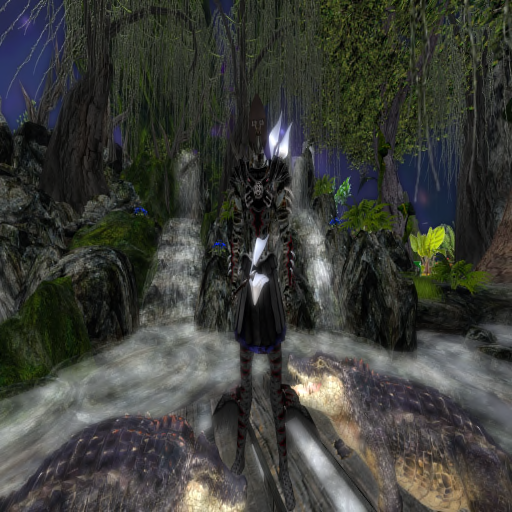

Something lunged out of the water in front of Leo. He jolted back. Bursts of white followed like a volley of cannonshots, heads clad in bullet-shaped helms like the ancient warriors his father had told him about, arms flashing with razor-fins, the water full of them. The spray caught Leo in the face. They reached up the launch’s sides, all shrieking to pierce the eardrums, and Billy let out a scream of his own.

The soldiers and sailors shouted, cursed, hacking with battle-axes while those with carbines stood behind them and fired. The shots and the white flashes illuminated, for only an instant at a time, men like eels grasping the gunwales, raising themselves up streaming from the water—how strong would they have to be, to head miles against the current in all that iron?—swiping with those forearm-fins, or reeling back from an ax-blow. Cushing was everywhere, firing his revolver, shooting a beast in the mouth, splattering teeth and black slime.

Leo couldn’t see Billy in the melee. The dark silhouette of a sea-creep sprang up in front of him, raising an arm. Leo swung his ax. The blade sliced through its forearm-fin and sank into flesh, hitting bone like a rock, the thing shrieking in his ear. He put his free hand to its breastplate—surprisingly smooth, like they’d buffed and polished it—and shoved it back into the water.

The creeps fell back, slid beneath the surface. The gentle rippling of the current returned. It was as though nothing had happened.

Leo crouched, chest rising and falling, sweating underneath his uniform. “Billy,” he puffed.

“I’m here Leo!”

Shouted out, just like always—why couldn’t the cuss ever just talk normally? “Did you see, I got me one, a big one! Twice as big as the other—”

Damn it, boy, when will you learn? Billy was too small, too frail and too aware of it; when they were boys Leo would hit him, but he never hit back; he’d been bullied, but never fought back. He should have stayed at home, he was too young for this. Now….

Daniel was talking—Leo had forgotten about him. The negro spoke as calmly as Leo wished Billy would. “Surprised me, Massa Cushing, but I don’t see everything. Those were its guards. Best be ready.”

The Lieutenant, hatless now with hair down to his collar, already stood at the bow working the davit. He seemed to favor his left arm. Leo wanted to help him, but…there, two of the neckerchief-wearing Yank sailors had stepped in. Leo sighed with relief. Federal sailors and Rebel soldiers, whose idea was all this anyway?

The spar, with its much-decorated torpedo, splashed into the water. It was tipped with a barb; in a normal war it could be stuck to an enemy’s hull. Then you backed away, pulled a lanyard, and set it off.

Daniel was still talking: “The guards, they make a circle all around it, and we was gettin’ through.” He paused. “It’s decided to handle us itself.”

Cushing looked over his shoulder. “It’s coming up?”

Coming up. Yes. If we could get the torpedo underneath it—

Billy screamed again.

Like a whale surfacing, it rose streaming from the water. In the starlight its skin appeared to crawl. Blind Daniel had seen this: sea-creeps of another kind, dozens of them, like turtles and men all mangled and squashed together. And dwelling in their midst, as if in some unnatural womb, the target.

“Corporal!”

Leo almost jumped—Cushing was addressing him. “My arm—slashed—just need a little assist—”

For Pete’s sake! Why can’t one of his own sailors—Leo grabbed the spar, held it steady, eased it down at Cushing’s direction, while the remaining carbine shots banged and others threw their axes at the glistening, roiling mass, the thing rising higher, blocking out the lowest stars, then higher ones, then higher still.

Leo felt Cushing tense beside him, groping for the lanyard.

Now—

Billy crashed sobbing into Leo’s arms, knocked the Lieutenant off balance. “I’m sorry Leo, I’m sorry—”

“Billy!” Leo wrestled with him. Cushing was thrashing his injured arm.

“—I never did it, you know that, never even seen one, I just figured maybe if everyone thought I was brave I really would be brave—”

Leo wanted to reassure his brother, to tell him all men are afraid in battle, it doesn’t make you a coward, you just gotta admit it that’s all, don’t go bragging or making things up, that’s why no one’s ever respected you—but no time. The thing was a wriggling wall before them now, smelling of fish and rotten seaweed, and Leo thought he could see the crawly things parting to make an opening like the mouth of a cave, wider, wider, could it swallow us whole—

He shoved his whimpering brother out of the way. Cushing regained his hold on the lanyard, pulled.

The blast threw Leo into the air. He saw nothing but white like the whole river churning, and tattered bits of that larva-queen or whatever it was supposed to be. He hung suspended forever in a shower of drops, pieces of flesh striking wet on his clothes, his face, and then he smacked the surface flat on his back, knocking out what wind remained, and the cool Mississippi swallowed him up.

He sank down, stunned; he was not concerned; in a moment he would regain his senses and kick up to the surface. It was over. He prayed it was over. If Daniel was right, the sea-creeps wouldn’t be too much trouble now.

Other thoughts returned. Suddenly he wished he could remain here below. He envied those damned things. They could call it off now, whatever their reasons had been. They could drift with the current, ease back out to the Gulf and the Atlantic and their undersea universe where explosions and cannons, battles and bayonet-charges could never follow them or disrupt their lives.

Unlike us….

Douglas Kolacki began writing while stationed with the Navy in Naples, Italy. He now lives and writes in Providence, Rhode Island, where he has placed stories in such publications as Weird Tales, Dreams & Visions and The Lorelei Signal.