Another Alexandria Next Tuesday

Another Alexandria Next Tuesday

By

Daniel Stride

To be, or not to be—that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms…

Its point needle-sharp, the rubber on the end unsmudged, Anthony’s pencil hovered over the paper. He knew the rest of the soliloquy, of course. Everyone did: it was government policy. But I’m from the generation who can still write it.

He looked over at the oak door, noting the polished bronze plaque had gone. He’d never given it much thought before. Ministers came and went, the name on the door changed—same gleam, different boss—but now there were only the tiny holes where the screws had been. Not Sir Simon’s fault. Not anyone’s fault, really. There was vanishingly little point in teaching literacy these days—not when memorisation was the name of the game. Why, there were now Ministry of Justice sub-committees where the sole membership requirement was reciting pi to a thousand decimal places.

Anthony shrugged, and wrote “against” in the cursive style his mother once thought so beautiful. No sooner had the pencil-lead left the paper than the quoted lines began to fade. Not with some flash of light or mysterious mist, but quietly and without fuss. Soon, there was once more a blank, lined diary page from 1975. Or perhaps 1976. He hadn’t needed to remember the year when he’d bought it.

The door creaked open; Anthony returned pencil and diary to the breast pocket of his tweed jacket.

“Atkinson!” The flushed potato face of the Minister beamed across at him. “Sorry to have kept you! On the phone, you know.”

Anthony nodded, and followed the man into the office. He felt like an attendee at a funeral.

Sir Simon’s shelves stood empty; the entire office consisted of a desk, three chairs, two telephones, and a plate of thickly-buttered toast. The curtains were pulled back; the Minister even had a window open, letting in the murmur of the street below.

“Quite the spartan look,” said Anthony. He settled into a chair.

“Yes,” said Sir Simon. “I’m a realist.”

Anthony’s fingers toyed with the lucky pencil-sharpener in his trouser pocket. “You don’t think the boffins down in the Burrows Street lab will find something to save us?”

Sir Simon laughed. “Really, Atkinson? The time for a cure was twenty years ago.”

He’s right, of course. When this phenomenon first appeared, it had only wiped older words and recordings. Tragic in itself: no more Jane Austen or Charles Dickens, save for snatches afficionados still recalled for a wager, but there was no disruption of everyday life. Then, over the ensuing two and a half decades, the mysterous wipings became ever more severe. As of last September—the morning of Tuesday the 22nd, to be exact—nearly all information older than five years had vanished. Copying was no use, and despite limitless government funding, the greatest brains in the world had as yet found no solution.

“So,” said Sir Simon. “Down to business. We don’t know how bad next Tuesday will be, but we ought to assume the worst.”

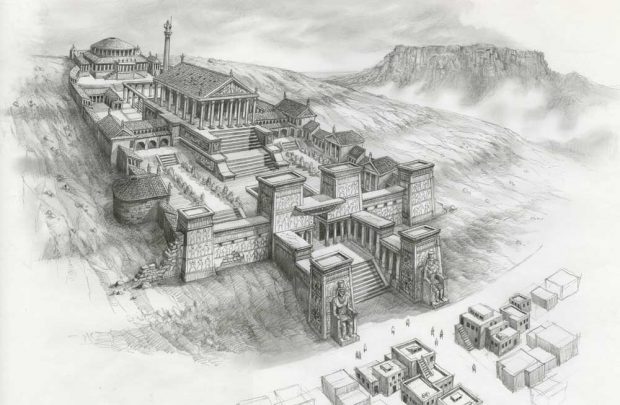

“Another Alexandria,” murmured Anthony.

Sir Simon cocked his head. “Pardon?”

“Nothing, Minister,” said Anthony. “Please continue.”

“As I was saying, if the worst comes next Tuesday, there will be no ability to preserve information external to the human mind. So my colleagues and I are formally disbanding the Department.”

Anthony blinked. He had suspected this, but to hear it expressed so casually….

“You would put me out of a job?”

Sir Simon laughed. “No, no, Atkinson. Simply shifting your responsibilities. In this new age of purely oral transmission, centralised structures make little sense. As of next week, you will report to your local council. Basingstoke, I believe?”

Anthony nodded.

“Don’t look so glum, Atkinson. It’s not the end of the world, no matter what the Home Office says!”

Anthony grimaced. “In one sense it is, Minister. The end of the world I knew.”

Sir Simon smiled. “Ten years ago, even five, I felt much the same. That the rug had been pulled from under us. No computer gadgets, no bright future of information technology. No books, films, or television, even! But no use crying over spilt milk—the human race was around millennia before writing, and we’ll be around for millennia afterwards. We still have sketches, sculptures, and paintings, if not photographs, words, or numerical representations. We still have the Queen’s face on the ten pound note….”

“Even if we’ll only tell the denomination from the colour.”

“Quite, Atkinson. I dare say you are one of the lucky ones. Think of the paper mills, lawyers, and newspaper reporters. Think of the scientists, accountants, and romance novelists. The ministers of religion, now that the old King James has met its maker. Why even I…” Sir Simon adjusted his spectacles. “What use is there for Westminster and Whitehall now? What use is there in a single nation? We can only reach the people through live radio broadcast! No, it must be this way.”

“Yes, Minister.”

Sir Simon nodded. “Now, excuse me. I need to telephone the Education Secretary. She informs me there are some memorisation techniques involving the Hindu Vedas…”

#

The Sackville Road sign may have gone, but the street’s identity remained: the locals hung hempen bags from the lampposts. Such are the times.

Anthony sighed, and boarded the twilight bus home. He flashed his departmental transport pass at the driver—the last time he’d use the pass, he realised: next week he’d have to dust the cobwebs off his bicycle. The only other passenger, a wrinkled lady in horn-rimmed glasses and a beige cardigan, was staring into space, as though she too struggled to comprehend what was happening to the world. Anthony wandered down to the back of the bus. He chose a seat beside the window, three seats up from the rear.

Outside, braving the cool air of late autumn, the shopkeepers were closing up. The man from Arnold’s Curiosities wiped the chalk from his sandwich board, and dragged it inside. By this time next week, there’ll be no board at all. Anthony frowned. What then? Navigating one’s way around would rely entirely on experience. Yesterday, he had helped a Bavarian woman find the butchers—imagine that, a tourist in this day and age!—but soon everyone would need directions. Perhaps Sir Simon was right, perhaps the future was local. A stable life and a stable job, an allotment for growing potatoes and swedes, and no venturing more than a hundred miles from home ever again. So different from what he’d been promised as a boy.

Martin Gregor got on at Melville Street. He wore a broad-brimmed hat, and a ridiculously long knitted scarf. Anthony raised an eyebrow as his next-door neighbour sat down beside him.

“What’s the occasion, Martin?”

The man removed his hat, and brushed off a red oak leaf that had attached itself to the band.

“I’m off to a Farewell.”

“A Farewell?”

“For Doctor Who. If the wiping next Tuesday is as bad as everyone thinks, this will be the final episode. Ever. So Bill and me are saying goodbye to the last year’s worth of serials.” Martin shrugged.

“You can come too, if you like. Costume’s optional.”

Anthony shook his head. “I have other plans.”

In truth he didn’t, but Anthony had never been a fan. Still, with so much culture disappearing off into the sunset, Martin would not be alone.

The bus stopped at the Melville Street traffic lights.

“The funny thing about Whovians,” said Martin, “is the younger crowd. Not the kids, but the ones just old enough to go to conventions and so forth. They don’t think it’s the end.”

Anthony silently prayed for the lights to turn green. “Oh?”

“They think you don’t need television or books. Getting together and telling a made-up monster story is enough. Perhaps they’ll even act it out, impromptu, on a stage or in the park. That’s as much Doctor Who to them as Genesis of the Daleks was to me. Funny, isn’t it? Bill’s nephew runs a Doctor Who puppet show on Saturday afternoons. Imagine Punch and Judy as the Doctor and his companion….”

The lights changed. Anthony muttered thanks to whichever merciful god was responsible.

#

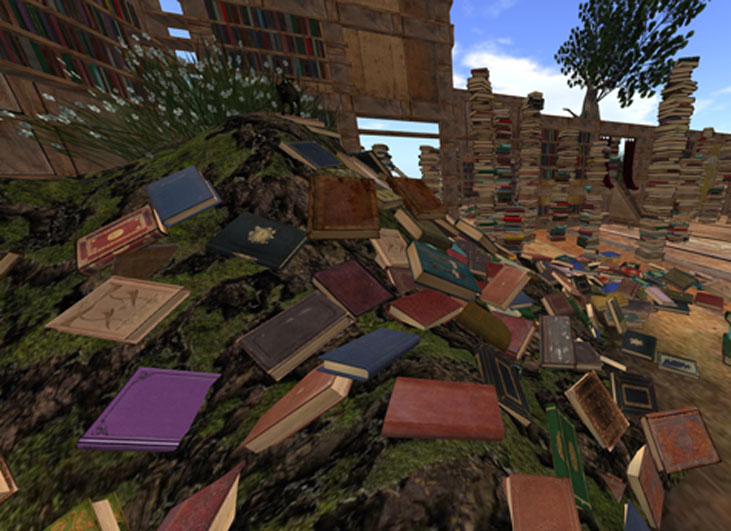

Standing on tiptoes, Anthony pulled the book down from the shelf. Fahrenheit 451, judging by the dust jacket, though the title itself had vanished. It’d been years since he’d read Bradbury, not since he and Susan made that New Year’s resolution to try proper novels again. So I read this, and she read Moby Dick. I think. Now he would never read anything again.

He thumbed through the blank pages, trying and failing to muster outrage. There were no remaining books older than five years—next Tuesday, there might be no books at all—so where was the grand dystopia, the bread and circuses, the gleaming leather jackboots and the unsmiling propaganda posters? Nowhere. Life pottered on, leaving someone of Anthony’s generation behind. Why, it wasn’t even government’s doing: Sir Simon and his lot were clueless as anyone. A travesty, a crime dwarfing the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, yet no-one was responsible, and as the years had passed, fewer people even cared.

Anthony returned the book to the shelf, and went to the kitchen for a cup of Earl Grey.

He was pouring in the milk—Harry and Margaret across the street owned twin nanny goats, and cheerfully swapped milk for jam—when he heard the front door shut.

“I’m home, dear!”

Susan came through, fidgeting with a leather handbag. The one he had bought her during their honeymoon in Brighton all those years ago.

Anthony shovelled a flat teaspoon of sugar into his cup, and stirred. “How was work?”

Susan grinned. “You know how it is. Getting the little ones to memorise Kings of France and Prime Ministers of Canada, with stories to link them all together. Not the history classes of my era, of course. History as a narrative would have old Dr Flynn rolling over in his grave. Whiggery or worse, he’d say.”

Anthony sipped his tea. “But it’s that or nothing.”

“Of course.” Susan extracted a Maldon salt tin from her handbag, and deposited it on the wide shelf beneath the spring onions and the jars of home-made blueberry jam. “Oral tradition is better than no tradition, and the students do respond. One of them, Amy Taylor, Brenda’s daughter, can recite the Kings of Wessex like she’s listing the days of the week. She’s eleven.”

Anthony took another sip. “Without knowing anything about the world that birthed those Kings. It’s a meaningless list of names.”

“A list of names, yes. Meaningless, no. Amy and her classmates attach stories to each reign. Children think in parables now, Anthony—not in terms of Whiggery or inevitable progress, but in terms of lessons. It’s not at all historically accurate, but even Dr. Flynn wouldn’t call it useless, not for the world they’ll be living in. It’s a different sort of knowledge from what you and I grew up with: new and yet strangely old.”

Anthony finished his tea. Putting the cup down on the William Morris table mat, he drew a deep breath.

“Sir Simon’s kicking me from the Department down to local council level. Whitehall thinks there might be nothing left on Tuesday.”

“They’re probably right.” There was a clinking of glass as Susan shifted jars around the pantry. “I’m surprised they didn’t move you earlier.”

“Sue,” said Anthony. He tried to keep his voice calm. “The Department was my life. It’s all I’ve known since University.”

She turned and looked at him, a sad smile on her lips. “I know, dear.”

“You remember when they promoted that fresh-faced twenty-something over me? Because I read the Classics at Leeds, rather than Oxbridge? I didn’t care: I enjoyed where I was. Now…” He hung his head. “The future terrifies me, Sue. What if Basingstoke Borough Council have no use for a middle-aged administrator? What if they find another fresh-faced twenty-something more skilled in memorisation? I’m facing my own funeral, without even a headstone and a bundle of white roses to mark my grave. What can I do in a world without reading and writing?”

Susan strode over and hugged him. Her embrace felt warm and comforting.

“You can live, Anthony. It’s not the end. It’s the start of something different, and we’ll be around to see it. Think on that. Treasure it.”

Anthony smiled, and rubbed his hand over the back of her cashmere jersey. “I’m Classics, and you’re History. Quite the pair of fossils, aren’t we?”

She pulled away. “That we are. But the old world’s not buried yet—and now is the time for fossils.” She flashed another toothy grin. “If you don’t believe me, Doris Bates’ English class are putting on a production of Beowulf tonight, in actual Anglo-Saxon. What’s say we fix ourselves something quick—cheese and gherkin sandwiches, say—and stroll down to the Community Hall later?”

#

Hands behind his head, Anthony lay staring at the dark bedroom ceiling. His first Monday at Basingstoke hadn’t been as bad as he’d feared, though he couldn’t shake the feeling the younger staff were humouring this has-been from yesterday’s Civil Service. Maybe tomorrow’s wiping wouldn’t be the end either? Don’t get your hopes up, old man.

Susan snored softly. He glanced at his wife’s shadowy form, her back turned towards him. She’s asleep. It’s now or never.

Silent as the grave, Anthony slipped out of bed, into his slippers. Giving the creaky floorboard a wide berth, he crept across to the cupboard and donned his tartan dressing gown. Then he tiptoed from the bedroom. He didn’t dare shut the door; those hinges would wake Harry, Margaret, and their goats, never mind Susan. Serves me right for not oiling them. Too late now.

Coming to the living room, Anthony tugged back the curtain to let in moonlight. It was a full moon tonight, and it bathed the room in a soothing silvery glow. Anthony pulled down the Bradbury from the bookshelf. His heart beat faster. Yes, it was still there: wedged between the fourth and fifth pages was the wedding anniversary card he’d bought from Arnold’s Curiosities. No-one bought cards any more—why would they? Even the shopkeeper at Arnold’s had looked at him strangely, no doubt wondering why this gentleman was paying 5p for something soon to become a slab of worthless cardboard.

Anthony fetched a pencil from the mantelpiece, sat down at the coffee table, and inscribed:

My dearest Susan. Thirty-five years ago, you made me the happiest man in the world. I still treasure every moment of your companionship, your kindness, and your love.

Anthony.

Yes, that should do it.

He left the card sitting on the kitchen table, next to the teapot. Then he paused. Wasn’t this just simple vanity? Come tomorrow morning, his words would be erased from existence, along with every other bit of writing in the world. Maybe he ought to have done the normal thing and bought Susan a bouquet from the corner florist. White or red roses were always popular.

But that wouldn’t be who I am. Regardless of what was coming on Tuesday, he had always treasured the written word. Even if no-one else in England still did, even if there would soon be nothing left to treasure. Behind the smiling stoicism, he knew Susan felt the same way: if this were vanity, it was a vanity they both shared.

Holding that thought, Anthony returned to bed, and to his still-snoring wife.

#

He awoke to the dawn siren over Basingstoke.

Yawning, he sat up and rubbed sleep from his eyes. The bed beside him was empty, but that was hardly surprising: Susan was a morning person, a lark, rising before the hated community alarm clock shook everyone else awake. I’m a crotchety old barn-owl. My time is the evening.

He climbed out of bed, and stretched. Then, putting on his slippers and dressing gown, he wandered through to the kitchen for a hot cup of tea. And perhaps a surprise. Part of him, the idealistic part, hoped the anniversary card still bore his inscription from last night. The realistic part, the Sir Simon of his mind, ordered him to stop such nonsense. Like a strange inversion of Christmas, his groggy mind mused: the best present would be nothing at all.

Already dressed for a day’s teaching, Susan sat at the kitchen table. Spoon in hand, she munched away on a bowl of home-made muesli.

“Morning, dear,” she said.

“Morning.” Anthony filled the kettle from the tap, and switched it on.

“Thank you for the card. It’s made my day. Such a lovely, old-fashioned gesture.”

Anthony’s palms twitched. “You read it?”

“Of course, I read it, dear. It is our thirty-fifth wedding anniversary.”

His jaw dropped. “You mean… it wasn’t erased? That we’ve escaped the wiping?”

Susan put down her spoon, and smiled like the sphinx.

“I may have read it in your heart; I may have read it on the page. It’s not important.”

“It is important.” Anthony repressed the urge to shout. “It’s the most important and miserable day of our lives. Imagine it—a world without words. It’s a horrible, unspeakable tragedy!”

“Calm down, dear. If it’s a world without words, what are we doing now?”

“You know what I mean!”

Susan steepled her fingers. “A world without writing would be bad, but it’s better than a world without thoughts and feelings. We’ll always have those, you and I. We’ll still express them, just as you did with that card.”

Anthony blinked.

“You see, dear, no matter what happens today, or the future, I am blessed with the best of husbands. What wife could expect an anniversary card on this of all mornings? I couldn’t ask for more.”

The next thing he knew, she was hugging him. Tears ran down his cheeks.

“Thank you, Sue,” he whispered. “Thank you.”

Daniel Stride has a lifelong love of literature in general and speculative fiction in particular. He writes both short stories and poetry; his first novel, Wise Phuul, was published in November 2016, by small UK press, Inspired Quill. Daniel lives in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Website: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/

Publications: https://phuulishfellow.wordpress.com/bibliography/