The Restaurant at the End of the War

The Restaurant at the End of the War

By

Clint Spivey

“You’re going to feed the greasies?”

Wallroy cringed at the slur while watching Ledger’s finger, so near the transfer button, pause.

The Ledger was where one came for cash when the banks on Stain refused. Behind the balding loan shark stood two women who, beneath the smog-smeared dome of the Centauri-Two-Three colony, were known only as Meat and Hook. In a dome where undesirable men outnumbered women three-to-one, the two enforcer lovers made for a pair no less frightening than any Sacred Theban Soldier. Meat was a simple, two meter tree-trunk, her burly arms folded in boredom while she glared at Wallroy in hopes of future beatings. The rail-thin Hook beside her was rumored to hide implants beneath her manicured nails as lethal as they were pricey.

“I’ve secured four containers of Mewlani food, Sir,” Wallroy said, defaulting to his old Army lingo to show respect. “We got a great location within walking distance of The Needle.”

The Ledger leaned back in his chair, the transfer button still glaring red.

“You’re really going to feed those fleabags?”

Wallroy beamed. “And make a cute Kroner while doing it.”

“You’d better,” Ledger said before swiping the transfer green.

Hook smiled while Meat just glared.

#

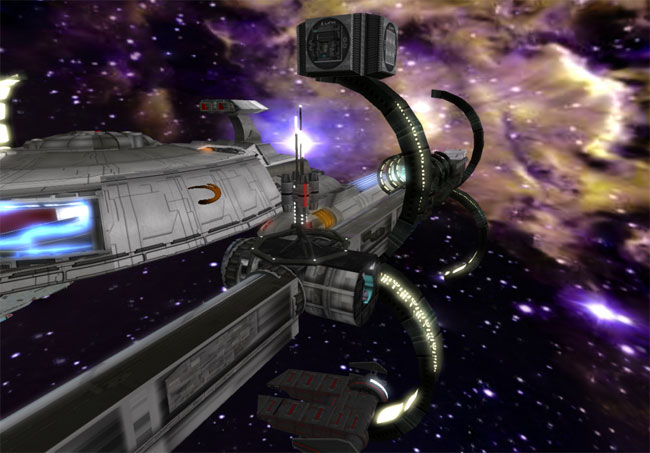

Proxima burned red through the perpetual smog clouding Stain’s dome. Once called Sustain by its founders, the recycled pollution of three thousand humans grasping for life had made the shortened name far more applicable. Skewering the dome’s center was The Needle, Stain’s lone elevator reaching to orbit.

Ledger’s cash had secured a spot on the corner of Prosperity and Empire, a twenty minute walk from The Needle. Like most places on Stain the streets retained their title from when the colony was a high-end business venture. Now, each shadow required scrutiny as they likely concealed meth-addicts waiting to pounce and demand your wallet. The abandoned people lingering before vacant storefronts reminded Wallroy all too much of the Hellas Planitia slums on Ares where he’d grown up.

His own establishment hadn’t escaped such a fate. A woman wearing about a dozen jackets sat congealing like amber near his rented property. A paper cup with a few coins sat in front of her.

“We don’t open for a few days, you know,” Wallroy said. He shook a cigarette free from his pack and dropped it inside her cup. Wallroy saw her grin as he entered the restaurant.

“She will come back if you feed her,” said Blistren, Wallroy’s Mewlani partner.

It was just a smoke.” Wallroy shrugged. “What can I say, she melted my heart.”

One of the few Mewlawni on Stain, the hairy blonde alien towered from behind the restaurant-counter. The Mewlani, humanity’s enemy for almost ten years, looked to be completely comprised of hair. Blistren’s was a dirty blonde. Trimmed and kept neat to reveal his two eyes and crooked-teeth, he kept the length tied back in a tail.

Blistren hailed from one of the outer regions of Mewlani space that had accepted human bribes to sit out the fighting. The two had spent the war working in the same army kitchen, where, over steaming steel cauldrons big enough to bathe in, the two had first discussed starting a business.

They’d decided on, ‘Sluice,’ a name Blistren swore had deeper meaning in Mewlani. Eight booths wrapped around the L-shaped restaurant with seven counter-stools forming the long part of that letter. Puce must have been a popular color once on Stain because every speckled formica table and puffy seat claimed some purplish-brown shade of it. Blistren and Wallroy had crammed beds into the two tiny rooms above the restaurant until they could afford an actual apartment.

“You should check your messages,” Blistren said. “Because we haven’t received the slange.”

Blistren flashed the message from The Needle Port Authority to the monitor near the register. Wallroy grimaced while reading of their impounded containers.

“I thought we handled the paper-work,” Blistren said.

“We did. All of it.” Wallroy had spent hours wading through the various online forms and documents the locals had thrust upon him. No sooner had he satisfied one requirement before the authorities conjured up two more to stall Sluice’s opening. “This must be a mistake.”

“Hope that’s a mistake, too.” He pointed a stubby finger at the amount the authorities were demanding to relinquish their property.

Wallroy thought of The Ledger when he saw the price. Was this his doing? Or simply another bureaucratic block thrown in their path?

“I hope so, too,” Wallroy said.

#

“But I’ve already paid,” Wallroy pleaded to the uninterested man working the desk. Through the dingy window, in the fenced yards beside The Needle vanishing into orbit, Wallroy could see his containers.

“You’re one opening the restaurant?” the bearded man asked. “For the Mewlani?” He gave Wallroy a single, dismissive glance before turning back to the movie on his tablet. “You paid for storage but not the handling fee.”

Twenty minutes of threats followed by haggling hadn’t lowered the price a single kroner. When it looked like he wouldn’t have access to the key item his nascent menu required, Wallroy relented and fumingly transferred the fee from his account and asked when he could take his containers.

“Only licensed agents can load and unload Needle goods.” He flashed a delivery service to the window display. The company miraculously shared the same surname as the helpful man currently assisting him.

It was another five days before they received their slange. The gel-like substance was a Mewlani staple that could be served thickened in stew or thinned to soup. While the Mewlani had a diet as varied as humans, slange was as ubiquitous as rice or bread. And Wallroy now had nearly one metric tonne of the stuff.

Fearing a humanitarian crisis during the war, the army had secured enough slange from friendly Mewlani parties to ensure adequate supplies for the accumulating enemy prisoners. Leave it to humans; they may drop a thousand tonnes of tungsten rods from orbit, pounding women and children to mist, but they’d at least provide the survivors with culturally appropriate food. Anything less would be insensitive.

“I’m going to bed.” Blistren stomped upstairs after they’d finished unloading the slange, which had arrived just before midnight. The ‘Sol Gvt.’ stamped cardboard boxes filled Sluice’s walk-in refrigerator to the ceiling. Wallroy closed the walk-in, and lit his last smoke of the day.

“Those things’ll kill you.”

“Jesus!” He choked on his drag at the silken-steel voice. Hook, wearing a jumpsuit that looked vacuum-sealed to her wiry frame, watched him from a corner, a ghostly blue halo glowing from her implants.

“Tomorrow’s the day,” she said stepping from the shadows.

“Then why are you here tonight?” he asked before taking a trembling drag.

“Call it a service. A reminder to keep things running smoothly.”

“The Ledge’ll get his cash tomorr—” Wallroy froze as a curving claw popped from Hook’s index finger millimeters from his left-eye.

“Mr. Ledger.” she said as his cigarette fell to the floor.

“I’ll transfer the cash first thing tomorrow,” he said.

“That’s the spirit. I’d hate to leave this somewhere.”

Like a striking snake her hand was down the back of his pants. Wallroy’s brief confusion vanished as her blade poked flesh far too near a region where sharp, foreign objects ought never to be.

“You see,” Hook purred close to his ear. “These darn things are detachable. I once lost one within a guy about, oh, seven centimeters deeper than this one here. I hear he had to drag himself to help by his fingers to avoid any…uncomfortable movements that might have lodged my errant little nail further. The paramedics thought the babbling fool was gakked out on meth. When they jerked him onto the stretcher, I could hear him screaming all the way back at Mr. Ledger’s place.”

She withdrew her hand. “First thing tomorrow with the cash.”

By the time he plucked his still smoldering cigarette from the floor, she was gone. Puffing down to the filter, he prayed the first refugee transport arrived on schedule.

#

SNS ibn Aziz sat like a gorging tick against The Needle. Just barely visible at berth high above the dome, its running lights flashed red and green halos through Stain’s pollution. The beggar woman was back at her spot outside the restaurant while Wallroy watched the ship over his morning smoke.

“Look, Amber,” Wallroy said in absence of any name for the fossilizing treacle beside him. “I don’t mind you hanging out here, but would you mind relocating a bit that way?” He nodded toward Empire Street away from the entrance. “Do me that favor and you’ll have dinner each night with what we got left over.”

She offered a crooked grin when he dropped two cigarettes in her paper cup. Growing up in the sewer-pipe slums of Ares, Wallroy had learned which derelict humans were dangerous junkies and which weren’t. Amber, seemed much the latter and he had no problem offering olive branches and leftovers provided she didn’t leave piles of feces on his doorstep. She remained silent when he returned inside, but Wallroy noticed her scooting toward the corner a few minutes later.

It was after 15:00 when the first carriages surrounding The Needle began their descent. Wallroy felt the same excitement likely all on Stain did at the prospect of eager visitors arriving with fat wallets. Around 20:00, Sluice had its first customers.

“Fing kinzstreen,” Wallroy butchered the Mewlani pronunciation while handing out menus. “Welcome.”

He fought back laughter at the three Mewlani soldiers and their traditional warrior hairstyles. Mullets may have provided utility to Mewlani warriors during the centuries, but the warfighter-in-the-front, party-in-the-back remained as ridiculous as ever to a human. He now appreciated the hippie-coolness of Blistren’s simple pony-tail.

“We hear you have a Mewlani cook,” the shortest one said. “Is he good?”

“Best on all Sustain,” Wallroy said, defaulting to the colony’s proper title with his first customers.

“Slange stew?” another said as he looked over the menu’s Mewlani portion. “You get slange out here?”

Mewlani were amenable enough to plain, short-grain rice and human tubers—the main staples grown in bulk on Stain—as long as it came drenched in slange. The three placed their orders, and were quickly chatting among themselves.

“We’re officers,” the shortest one said as Wallroy made conversation after their second bowl each. “The locals here are still nervous having Mewlani walk their streets. But the MP’s aboard ibn Aziz allowed us a few hours groundside.”

They’d all been high ranking prisoners and were only now returning home with other refugees. They inquired about take-out orders and happily ordered six each. After paying, they departed with bags of steaming styrofoam clam-shells filled with Sluice’s best.

The short one shook Wallroy’s hand. “Please give our thanks to the cook.

Their only other customers were a gray-furred Mewlani family, two young girls and their parents.

Where the officers before them had salvaged some dignity in appearance—likely due to their station in the Mewlani military—this family was ragged. Nearly morbid with the remnants of whatever delousing they’d endured on the refugee transport, they dragged a biting stench of scouring, harsh chemicals. The children scratched constantly while the parents endured their itching in preservation of their dignity. Far from the lustrous, fragrant coat Blistren groomed each morning and night, the poor family was a matted, tangled mess.

Wallroy served their order and they were soon bent over steaming bowls. Blistren must have noticed their plight, for he emerged from the kitchen lugging a case of unopened Mewlani shampoo from the stacks he kept within his room. Without saying a word to the customers, he arranged the bottles neatly beside the register and tapped out a price on the menu board. The scrolling numbers announced a two-for-one bargain with every meal.

“Nice idea,” Wallroy commented later while sweeping the lobby. After paying for their meal, the family had happily scooped up a bottle for each member. Blistren offered a simple thumbs-up from his spot scrubbing behind the pick-up window.

Wallroy made a mental note to pick up some toys. If today was any indication of the transports, there would be more kids passing through and he wanted some impulse-buys ready at eye-level.

As if their first day had been far too pleasant, they had one, final visitor.

“You serve Mewlani?” the man asked in gruff tones.

Wallroy turned and froze. The man looked plain enough. T-shirt with some unknown logo, jeans, and a frayed ball-cap with a leaping bass on it. But Wallroy recognized the type instantly from his army days.

Muscles rippled beneath the shirt. Not the bulging meat-head ones for show, but the wiry kind which proved deceptively strong. The red hair and beard were cut just short enough to require little maintenance while remaining just south of army regs. Wallroy was surprised the ex-soldier wasn’t still wearing his boots.

“That’s right,” Wallroy said trying to feign nonchalance as he continued sweeping Mewlani hair across the linoleum. “We’ve got human food too.”

“You got a Mewlani cook?” He was looking about the place and not at Wallroy. “Serving slange?”

Just what he needed. Some uber-patriot veteran concerned with the carpet-bagger feeding Mewlani on his world.

“You really think you’re gonna pull off serving Mewlani? On Stain?” Still without once having looked at Wallroy, the man shrugged, and walked out.

“Another customer?” Blistren called from the back.

As if The Ledger’s lunatic enforcers weren’t enough, now they had a government-trained one to worry about.

#

The next day saw several more Mewlani customers, likely after being informed by the three soldiers the day before that the place was legit.

Wallroy made sure to heap their bowls to near overflow as he served. The smell was soothing and soon, the several families in the booths were chatting over their meals.

Wallroy saw Amber outside at the far corner, as well as a few people staring inside from the street.

“Kini’shen,” Wallroy garbled an ‘excuse me’ to the family nearest the drawstring for the blinds as he lowered them, providing some privacy.

Blistren emerged from the kitchen during a lull to converse with the patrons. Seemed both groups were eager for gossip and he had soon made the rounds at each table.

“I’ll be damned,” Wallroy muttered. Sure enough, as each family paid, they picked up a bottle of Mewlani shampoo at the register. By the end of the night, after the final few families had departed, Blistren had moved his entire supply, pocketing a hefty bit of cash.

“But what are you gonna do?” Wallroy asked as he wiped brown spots of dried slange from the counter.

“I’ve placed another order,” he said from the back. “I can use human stuff until then.”

The next six days, the entirety of the ibn-Aziz’ port visit, saw Sluice filled with customers. By the ship’s final day in port, Sluice had served nearly three hundred Mewlani families, earning enough for its first three months of rent as well as almost two months of Ledger’s payments, with a small amount going beyond the juice toward the principle.

It was that last day, while watching a satisfied family depart, that Wallroy noticed the crowd outside. With the blinds kept closed, it wasn’t until he moved to the glass doors that he saw the street was filled with people more than curious. The departing Mewlani refugee family endured shrill insults as they hurried their children to safety.

“What is this?” Wallroy said after emerging onto the sidewalk.

“You got some problem serving Sol food?” A man jabbed a finger into Wallroy’s chest.

“We only import the slange,” Wallroy said. “Everything else we buy local.”

“And what happens when they decide to stay?” a woman asked. “When they’re not just wandering to your shack?”

“You too good to hire humans?” A man called from the crowd.

Others added their protests as Wallroy suddenly stiffened to the danger. The swelling crowd lacked but the spark to erupt into a mob.

“Look, I’m just running a business is all.” He held up both hands in a placating gesture.

“Go back to Mewlan, greasies!” Someone shrieked.

Wallroy turned to see another Mewlani family frozen in fear at the doors. Things happened fast then. The crowd pressed upon them, hands grasping for Wallroy as well as the Mewlani. Wallroy fought to push the family back inside, but blows landed all around him amidst the shouting. The Mewlani child shrieked as someone grabbed a handful of hair at the back of her neck. She wailed as Wallroy and the father pounded the arm away.

Fighting their way back inside, Wallroy noticed a woman recording the incident. Wearing a black beret atop pixie-cut hair, she held a recording drone above the crowd, its spidery legs fully extended while the orb atop its head recorded everything. Amber sat in her usual spot, muttering to herself with her hands over her ears.

“Close the shutters!” Wallroy screamed after finally pushing his way back inside. He locked the door while screaming faces fogged the glass millimeters away. Blistren ran in back and soon, the metal security blinds were screeching down outside.

Wallroy turned and saw a dozen Mewlani looking right at him while the parents of the family he’d helped back inside comforted their shaking daughter.

At a loss, Wallroy grabbed one of the items he’d stocked near the register, an origami set with two smart-sheets. He removed one and demonstrated it to the trembling child. Wallroy snapped one of the raised divots lining the bottom and it folded itself into a neat little crane, the wings flexing out the last of the sheet’s meager charge like a butterfly settling on a flower. The girl accepted the offering but that did little to blunt the fearful stares the other patrons focused towards Wallroy.

Later, after the police had cleared the streets, and assigned several burly security drones to escort the refugees back to The Needle, a single officer stayed behind.

“Cleaning up your mess is not our job,” he said. “You need your own security.” He pulled the badge from his chest and slapped the shield against the register. “Here’s your receipt for services rendered.”

Wallroy gaped at the outrageous number glowing from the register display. “Don’t you mean, bill?”

“You’ve wasted enough of our time. You’ll not waste more shirking payment. The funds have been withdrawn from your account. Standard procedure on Sustain.”

Gone was nearly every kroner they’d spent the last week earning. They might as well check the seat cushions and ask Amber outside to pitch in the contents of her paper cup. And even then, they’d likely still be short of Ledger’s weekly payment, which was due by morning.

#

Wallroy was glad he’d already gone to the bathroom the next morning. If he hadn’t…

“Rise and shine.”

He might have shit himself when Meat growled her entrance.

“Look,” he began. “It’s just a minor setback. The next transport arrives—”

Meat grabbed a handful of his shirt and dragged him close enough that he could smell the mint on her breath.

“Maybe Mr. Ledger is worried about his investment,” she growled.

“Let him go!” Blistren stomped downstairs. He grunted as Hook stepped from the shadows. Twisting the hair behind his neck, she yanked his head back while sweeping a claw toward his throat.

“Greasies should stay quiet when the adults are talking,” Hook said.

“Look!” Wallroy shouted, panic rising in his voice. “I can get the money.”

“Seems Stain’s a bit too rough for you,” Meat said looking around. “Fortunately, Mr. Ledger is willing to take this problem off your hands.”

“This problem?” Wallroy wasn’t sure what she meant.

“You can’t handle a business on Stain. Mr. Ledger can.”

“Now that we’ve built this business,” Blistren said. “Your boss comes in and takes it.”

The women both smiled as Wallroy realized what Blistren already had.

Hook, still holding Blistren in her augmented-iron grip, turned him to face her. “With such an eye for business, I doubt you’d miss if I plucked one out.” She raised the index finger of her free hand. A menacing six-centimeter claw flicked from the tip.

“Goddammit,” Wallroy shrieked. “Put him down you, fuck!”

“You all open?”

All four turned to the door at the new voice. Back was the red-bearded, army veteran from a few days prior, wearing the same tattered bass-master hat.

“Fuck off back the way you came,” Meat said. “This don’t concern you.”

“We’re here to eat,” the stranger said, his voice oddly calm.

Wallroy saw now he wasn’t alone. Behind the group of four other human men and three women—one with a pixie-cut beneath a black beret—stood over a dozen Mewlani men, women, and children. As if the scene could grow no stranger, Amber strolled up beside them.

“You wanna put them down, please?” Amber said.

Wallroy saw now, what he’d earlier assumed were simply piled on clothes when viewing Amber out front, was actually a frame rivaling Meat’s bulging physique.

“I said”—Meat tossed Wallroy against the counter like a stuffed toy—”to fuck off!”

She took one step before Amber stepped in front, looking as bored as ever while Meat tried—and failed—to stare her down.

“Alright you pieces of shit.” Hook released Blistren and moved toward the group, implants ablaze and claws rising from every finger. “You had your chance now you—” she froze, staring as her blades retracted and her implants went dark.

“That’s the thing with you civilians and all your fancy store-bought tech.” Amber waved a tiny black dongle in the air. “It comes standard with so many backdoors.”

“No!” Meat shrieked while lunging toward the group. She’d taken a single step before baseball-hat and another had an arm each bent behind her and had slammed her face to the counter. She glanced puzzled at Wallroy who could only shrug.

Don’t look at me I just run the place.

Hook, looking lost, remained still as Amber stepped close. “You go tell ol Ledge, that we’re gonna be by later to have a little chat. He might wanna rethink the way he handles this establishment.” Amber stepped aside while the other two released Meat. “We’ll be seeing ya’al again real soon.”

The two attempted intimidating stare-downs of the unimpressed interlopers for almost a minute before hurrying out.

“So.” Amber turned back to Wallroy, looking as flustered as having just scratched an itch. “Can we get some tables or what?”

#

There wasn’t a single empty seat or stool. Mewlani laughter, while subdued, filled Sluice. Children ran the aisles while their parents spoke to one another and the few humans sitting with them.

“The food’s not the best,” Wallroy said to the red-head sitting at the counter. “But for a Mewlani anything from home is better than nothing.”

“It’s fine.” He sipped his bottle of Stain Remover, the local craft beer.

“Can I ask. Who are you guys? Don’t see many humans with Mewlani.”

He took another drink before setting the bottle down. “They were our translators.” The man looked behind him. “Locals who worked with us during the war. Even with the war over, they’re pretty much hated on Mewlan. After all they did for us, we couldn’t leave them there.”

Wallroy cocked his head while handing a steaming bowl of stew across the bar to a waiting Mewlani woman with a young girl beside her. “Where are you taking them?”

“Back to Sol.”

“If they’re not liked on Mewlan or Stain, will it be much better on Earth?” Wallroy thought of every roadblock thrown in his way at merely serving the Mewlani food. Would Sol offer any warmer a welcome when Mewlani families started setting down roots?

“So that’s the solution?” Wallroy asked. “Bring them back to Earth and hope for the best?”

The soldier stared ahead for a moment before slumping his shoulders. The tough-guy persona vanished and he looked as confused as Wallroy had been since first stepping foot on Stain.

“I don’t know, man,” he said. “Solutions are like peace. They sell but who the hell is buying?” He drained the rest of his beer then pointed to the display fridge for another. Wallroy popped the cap then handed him the bottle.

The soldier took a long drink before continuing, “If we can help the few who want passage to Sol then that’s what we’ll do. Not sure if it solves anything but it’s a damn sight better than doing nothing.”

The man sat up straight, his doubt once more hidden beneath a ramrod military posture and blank expression. “Some of us own land. They can live there while their asylum claims are processed. Even if rejected, the government is welcome to try and make them leave. That’s why we brought Brighteyes over there.”

The young woman with the pixie-cut peeking from beneath her black beret continued interviewing Mewlani. Her camera-drone skittered about her shoulders, the orb atop its spindly legs filming the entire place in 300 degree panorama.

“She’s the media play in all this,” he said. “A real believer. She’s making a documentary that ought to win some hearts and assholes back home to our cause. And a couple of us worked with psyops during the fighting. If we could feed the Mewlani our bullshit, getting humans to swallow it will be easy enough.”

Wallroy just nodded.

“Amber, you call her?” He nodded to the woman Wallroy had assumed a vagrant. “She’s gonna be sticking around here as our liaison. She’s got more than enough security qualifications if local law enforcement tries to raid your accounts again. In fact, Brighteyes is interviewing local PD tomorrow. Might be you ought to inquire about being financially responsible for a near riot. Never know. When all Sol sees what you’re doing you might find that cash back in your pocket.”

‘Amber’ smiled from a few seats down and set three, unlit cigarettes on the counter.

“The war may be over, but there sure as shit isn’t peace in Mewlani space,” the man said. “There’s gonna be just as much traffic headed toward Mewlan than there is coming back from it. We’re putting the word out about this place. Make sure you’re open whenever Amber gives the word.”

“Absolutely,” Wallroy said.

The man nodded, staring absently past Wallroy. As if realizing something he looked down and dragged a finger beneath the counter. He held it up to reveal caked dirt and grime from the restaurant’s past life.

“And have the place ready for inspection next time.” He wiped the filth on Wallroy’s apron. “What the hell kind of joint you runnin here, soldier?”